The grant of a commercial television licence is a privilege of great public importance, especially to the people in the area in which the station is established; and there seems little doubt for its most effective use a commercial television station should, as far as possible, be in the hands or under the control of those people operating through the medium of a representative and independent company.

~ Australian Broadcasting Control Board (ABCB)

For six decades NBN Television’s news, programs, even commercials, raised the Hunter region’s community spirit.

It was not only our town, our region - it was our TV station.

Channel 3, NBN Television - or just “NBN” - was the gatherer and disseminator of all that mattered to us.

One could say that it ‘emanated’ the Hunter’s zeitgeist, that it formed a consensus experience and forged a collective identity more immediate and vibrant than its print and radio precursors.

NBN tightened the bonds of this relatively small commune, barely a half-million people clustered around a busy port, spread thin along a coastline, scattered through a valley and along the forested ranges that encircled it.

NBN brought into sharp focus the hopes and fears of our neighbours, their fortunes and fates. It was social media before that double-edged sword exposed us so sharply to diversity and so harshly to a polarised tribalism.

But when it came to local conflict, Channel 3’s relatively gentle exposure to division yet allowed good terms with the opposition.

The nightly news never sought to divide, and to this day our local news resists the cheap controversies of metropolitan broadcasters that only accelerate their decline to irrelevance.

Memory Lane

This is a photo essay of the early days, the first 13 years of “black and white” (monochrome) operation before colour television began in 1975.

It’s a small but surely valuable collection of images from times long gone, when the excitement of television infected those dedicated to producing it, and its creative novelty enthralled those viewing it.

Of the pictured, many are aged and retired while others, sadly, work (or star) in that big studio in the sky. They helped create the Hunter’s recent history and deserve at least this small tribute.

Feedback and Credits

Additions, corrections, and anecdotes are invited, either in the

comments section below, or via email to

Editor at

NewcastleOnHunter dot org

Anecdotes and educated

guesswork fill our story. But it was, after all, a lifetime ago.

This “living document” is informed by former NBN staff and you, our

marvellous viewers who supported the Hunter's very own television

station.

Early photographs are credited to Des Barry, who also trained staff to run the 16mm black and white film developing lab, and later ones to Lloyd Hissey - NBN’s stills photographers during this period. Stewart Osland and others must also deserve credit for this period. Do let us know.

Concept art for the proposed NBN Newcastle television studio.

The Creation

It was 61 years ago, as I write, that the entity NBN was conceived.

Newcastle Broadcasting and Television Corporation (NBTC) was established in May of 1958 when television licences were offered to regional Australia. Half the company shares had to be owned by “locals.” Though a small city, it was quite self-sufficient in millionaires.

$1.5 million construction project began in November 1961, NBN Newcastle-Hunter River Newcastle Broadcasting & Television Ltd

Granted: 17 July 1961

Commenced: 4 March 1962

Station program would issue from a studio complex built on three acres of land in Mosbri Crescent, Newcastle.

The call-letters “NBN” derived from the company's acronym NB(TC), with a trailing N representing New South Wales, as required by law. Unofficially, and to locals, it stood for Newcastle Broadcasting Network. Construction began immediately upon licence in November 1961, supervised by engineers from RCA (Radio Corporation of America).

The station would transmit on the VHF band (very high frequency) on a channel (number 3) that - to the eternal regret of so many technicians and engineers, but the delight and amusement of radio listeners - was right in the middle of the future FM radio band.

On Greater (Mount) Sugarloaf the transmitter site was prepared, comprising a transmitter building, a 142 meter tower (some documents say 138), and microwave links receiving program signals from the studio 22 kilometers to the east.

The Mosbri Crescent “studio” was two interconnected buildings. One, an actual studio with cameras, lights, and action, was a sound-insulated hangar-size space and the larger of the two.

The other rectangular building was a collection of departments, offices upstairs and operations on the ground floor. Over 70 separate operational compartments combined to produce the region’s entertainment.

They included administration, boardroom, sales, accounts, traffic, programming, promotions, commercial production, newsroom, news camera, art, film processing, film editing, telecine, videotape, presentation, master control, studio control rooms, dressing rooms, announcers booths, maintenance, props bay, aircon, lighting, and carpentry. And the gardener!

The Mosbri Crescent building in its first year or two. Landscaping is a handy guide to the passage of time.

You might reasonably assume lavish grounds were for the picnicking pleasure of staff during their long and extravagant meal breaks.

You might reasonably have thought I was joking.

First Contact

When NBN 3 was seen for the first time across the Newcastle region in 1962, we were already seasoned television viewers.

One day at Booragul in 1957, as a young cub scout doing his Bob-a-Job rounds for the Boolaroo troop, a kindly resident asked “Would you like to see a game of cricket being played inside a house?”

We young’uns rushed inside led by curiosity and followed by the amused householder to see ABN Channel 2 in Sydney broadcasting a game in brilliant black and white on a 19” Astor television set. I thought that Mum and Dad should buy one of these contraptions, and yesterday! It took nine long years to convince them.

Throughout Newcastle, Port Stephens, Lake Macquarie, Maitland, and some of the Hunter Valley, Sydney’s ATN 7, TCN 9, and ABN 2 were daily viewing.

Homes on the hills had steady reception most days, disrupted only by southerly changes or heavy rain. But on warm still nights when temperature inversions formed over the coast, TV reception from Sydney was picture-perfect for almost the entire Newcastle region.

And for those in the hollows with 10 or 20 meter masts and high-gain antennas, on those balmy nights a humble rabbit’s ears, even a wire coat hanger, would have sufficed.

So when NBN arrived, despite the fanfare and novelty… well, we’d seen it all before.

But what we hadn’t seen was a bursting forth of visual arts from local talent, film of community news and events, or the region’s intellectual capital adding its weight to our daily lives.

During the weeks leading up to opening night – 4th March 1962 – odd pictures appeared in those luckier homes when that clunky knob was rotated to number 3. Businesses that had displayed Sydney channels in their shop windows now showed what the curious were told was a “test pattern” or a “test card.”

Image by Bruce Langley, courtesy of daughter Pat Jones. It wasn’t until the thoughtful Pat Jones shared on Facebook, in July 2018, a photograph of NBN’s test pattern taken on the historic opening day, that answered what I had long wondered: which test card of so many did NBN use before launch date?

And at 6pm on that greatly anticipated night, the pattern gave way to real moving pictures from the heart of Newcastle itself.

The Postmaster-General C.W. Davidson officially opened Newcastle station, NBN3, during the station’s first program at 6.00pm on Sunday night, 4th March, 1962.

Murray Finlay then began his decades-long news reading career with our first local news bulletin at 6:30 pm.

Murray Finlay reads NBN 3’s first news bulletin live to air on opening night.

The sandbags were to stop the desk rolling away. Stage components are usually constructed on castors or wheels.

The “iconic” picture (top, above) has travelled far and wide. It was reproduced in multiples for promotional work. Its travelling companion below is less often seen.

The news was followed by The Phil Silvers Show at 7pm, and NBN's first movie, the 1937 movie Green Light, starring Errol Flynn.

The George Sanders Theatre series followed at 9pm, with the opening episode, The Man in the Elevator, followed by the first episode from the Halls of Ivy, then the first Mystery Theatre program, The Missing Head at 10pm.

Anglican Bishop James Housden gave the first evening meditation at 10.30pm, which marked the end of the first night of transmission for NBN.

Commercials on that first night included ads for Rothmans Cigarettes, Streets Ice Cream, Ampol, Commonwealth Bank, Shell, and W.D. and H.O. Wills, amongst other advertisers.

That first week, NBN set an Australian television record for most time spent on air in a week for a new station (56 hours).

In the lead-up to the launch, the station promised at least two movies a week (Thursdays at 8.30pm and Sundays at 7.30pm), as well as men's interest programs each Saturday afternoon between 3pm and 4pm. Women were well covered with programs in the early afternoon, followed by children's programming from 4.30pm to 6.30pm weekdays and more "adult" programming 30 minutes before closedown each night.

~ Wikpedia

Mt Sugarloaf and the Transmitter

Before getting lost among the generous supply of photographs of Mosbri Crescent’s ins and outs, something about the transmitter.

Program from the studio travelled 22 kilometres “line of sight” from microwave transmitters (“microwave links”) at the studio to microwave receivers at the transmitter site on Mount Sugarloaf.

Microwave links are identified by dish-shaped parabolic reflectors that direct the signal in a narrow beam, like a torch does with light.

This might be a good place to squeeze in a word about the studio side of those links. The image below is a rare photograph of equipment racks containing the microwave transmitters at the studio end.

Above ~ A rare photograph (print) of NBN's studio microwave link equipment racks, circa 1975. This is also representative of link equipment at the transmitter end.

For the record - as this might be the only such record - the center and right racks show the STLs (studio-transmitter link) at top of each. They were vacuum tube (“valve”) units and operated for over 20 years. They were almost certainly of RCA manufacture.

The rack second from left contains two links, a TVM6 and an FL4, for receiving remote broadcasts, mostly from the OB van. Top left a gauge shows nitrogen pressure in the waveguide/s feeding signal to the dish antennae, to prevent moisture ingress.

The area under the main RCA link (lower right) was a processing device and a sea of valves. Its functions I’ve forgotten.

What I haven’t forgotten is that one evening pictures off-air started to fade. Viewers wouldn’t greatly notice, but our studio receiver deliberately didn’t run automatic gain control (AGC) so it was pretty obvious.

I called the technician and watched to see how he would tackle this urgent (and to me complex) problem. It was an exercise in pragmatism. Out came a carton full of spare vacuum tubes and in they went, one after the other, till all were replaced

For a while after pictures never looked better off-air!

Back up on the hill and burning away in that mysterious bunker were two RCA TT-6AL transmitters, each generating 6 kilowatts of “RF” (radio-frequency) energy.

Photos from the hill are hard to come by. Staff photographers either didn’t know there was a transmitter, or were terrified of transmitter techs - probably the latter.

These poor-quality prints are better than nothing, and show a surviving RCA whose partner was torn out to make way for newer models. NBN subsequently deployed NEC and Thompson CSF transmitters.

Above ~ One of NBN's original RCA TT-6AL transmitters, retained as a backup for it's two replacements. Almost everything in a broadcast station has a backup.

Below ~ An amazing network of high-voltage radio-frequency coaxial ‘piping’ needed to handle mixing, filtering, tuning, and trapping of the TX output before feeding the antenna array far above on the tower.

The old RCA (further above) battled on into the 1980s as a standby transmitter.

Whenever a storm threatened Sugarloaf (every second day in summer, it seemed) we’d fire up the diesel generator and - for good measure - warm up the old RCA TT6AL too.

Sometimes when it went to air prematurely, its output level on our non-AGC receiver would show only 10% power on the oscilloscope as the power output tubes laboured to build emission from ageing filaments. As we described it in those agonising minutes: “the old thing is struggling to get up off its knees.”

But viewers mostly were oblivious as their TV sets made up the lost signal strength. Viewers farther afield, however, were busy thumping their TVs to improve the "snowy" picture.

The television program signal arriving at the Sugarloaf microwave receivers was fed to those RCA transmitters that operated “in parallel” – which means they both shared the work, and if one failed the other hopefully kept working till it was fixed.

Transmitter output then travelled out of the building and up a huge coaxial cable to the radiating elements atop the tower - the straight section where the tower stops narrowing in the photograph.

Top of the tower is 498 meters above sea level. The entire structure weighs 137 tonnes and sits on a 225 tonne concrete base. The orange and white colours - though fashionable, because all the towers wear them - provide daylight visibility for aircraft.

NBN transmitter building circa 1970. The groundskeeper, one suspects, has already lost a mower or two down the slopes by thoughtless parking.

NBN used to announce at the end of the day’s programs - around midnight when they literally switched off and the staff went home - that they were transmitting with a vision carrier of 100 thousand watts and a sound carrier of 20 thousand watts. This was effective radiated power (ERP) courtesy of antenna design and was not the actual power output of the transmitters.

Radiated power was in a narrow horizontal band, and very little went up into space, where it would be wasted. Also due to antenna design, power was skewed towards population centres and not sent equally in all direction.

Very little radiated power was aimed at the ground either, and so West Wallsend residents whose view of the tower was skyward had trouble getting a good reception, despite it being effectively in their backyards.

Both this and geography account for maps that show “coverage area” - a familiar term to people who have called to complain of reception problems.

NBN’s transmitter coverage area circa 1975.

Coverage area, hence reception, was greatly affected by mountains, local trees, weather, and transmitter antenna tuning that sent the signal where most people lived. Except Sydney!

Equally - something viewers did not want to know - reception was affected by faults at the receiving end, and during half a century of reception complaints it was rare that a householder could be convinced that their weather-beaten bird-roost of an antenna and water-soaked, rat-chewed cabling might be the issue.

The Studio Equipment

A note: Mosbri Crescent complex was referred to in its entirety by staff as “the studio” including, of course, the actual Studio A. You were, by now, probably wondering about that.

The Mosbri Crescent “studio” was, in 1962, two buildings. One, an office block upstairs and an operations and electronics center downstairs. The other, a large hangar-size structure. The famous Studio A where dreams were made, where news and entertainment were produced.

NBN Television studio Mosbri Crescent studio construction was concrete slab, steel frame, ribbed steel wall cladding, double-glazed aluminium windows, and corrugated asbestos roofing.

Almost the entire ground floor of the operations building was packed with equipment. Air conditioning plant, film processing, control rooms with vision switching and audio mixer desks, a “master control” where the pictures “to air” were processed, selected, and switched, and where “off air” (from the transmitter) was monitored.

There was film cutting and editing, videotape recording and playback, film-to-television “telecine chains,” “presentation” that switched programs to air according to a station log, generated by another department called Traffic that integrated commercials with program days in advance.

Rarely seen on public tours were rack upon rack of an incredible range of specialised electronics with disbelievable names, like sync pulse generator, time code, clamping amplifier or stab-amp (stabilising amplifier), routing switcher, distribution amplifier, and VITS (vertical interval test signal).

Sixty years ago broadcast television equipment was disproportionately expensive compared to similar electronics today.

Then the world market was smaller and TV broadcast stuff was huge and bulky and expensive to make. With little automation it was usually hand-constructed, often by engineers themselves. It required tedious tuning and rigorous testing before delivery. Television sets could be made by unskilled factory workers repetitiously soldering and assembling, but not specialist television broadcasting equipment.

Which is all to say that the brief shopping list below mentions only those large chunks of expensive capital plant, the big-ticket items. Turning them into a working television station required a complex array of additional smaller electronic items, rack after rack of them, and kilometres of wiring.

For each of these following items, imagine at the time of purchase but in today’s dollars that they cost from a half to several million dollars apiece. The initial 1962 shopping list was: three image orthicon cameras, one with a zoom lens; one vidicon camera; two telecine chains (to convert motion film to television program); one opaque scanner (for captions and graphics); an electronic special effects unit; a film processor (to develop motion camera film, not just stills); two videotape recorders; and two microwave links.

Add a fleet of vehicles, dozens of staff, sundries like pricey 16mm film cameras, endless consumables, fearful electricity bills…

An RCA 50mm projector converted photographic 'slides' mounted on a rotating drum into television signals.

The image above shows (at right) part of a photograph from one of NBN’s information booklets titled “Your Guide to NBN Channel 3.” It is Presentation suite, in which an operator – one of many through the decade, in this case Don Coles - switches program sources to air. Visible through the window is a drum-shaped unit in the adjacent room. This confirms that NBN’s original equipment included the RCA slide scanner shown at left.

It therefore confirms that the above-listed “Vidicon camera” was not a studio camera, but a bulky specially-designed unit fixed to the projector, which was, in the day, the only way to convert photographic film to electronic television signals.

Space and Expansion

NBN 3 took off like a rocket. It was irresistible to Novocastrians – well, to humans everywhere – and advertisers flocked to it, and the cash rolled in. It had to, as the place found itself on an endless rollercoaster of expansion and technical upgrades that simply never ceased.

So, the first discovery made by management and staff was probably on day two of transmission - that the hiring of one extra person above the initial crew created an immediate space problem!

What was a generous parking lot on the building’s eastern side (along the centre, below) was quickly consumed by extensions, especially during planning in the late 60s for the inevitable colour equipment that would need to work alongside existing black and white electronics. An operational nightmare, essentially needing to have two separate program paths and their separate equipment running at the same time for the switch-over to colour.

Rear (eastern side, looking south) of NBN Television studios in Mosbri Crescent Newcastle. Circa 1965. This shows the original buildings. Studio A just visible at top right, central complex center-right, its nearer end contained air-con plant and props bay. Garage and carpenter's workshop at left.

That also meant a new colour film laboratory, quite an extravagance, but without which NBN’s nightly news would not greatly impress running black and white stories.

When an Outside Broadcast (OB) vehicle was bought, a garage was built out front in Mosbri. When the newsroom occupied that garage, having vacated the lower rear of the building, the OB truck displaced their news cars from the rear garage.

I can’t reconcile the front and rear OB garages’ timelines. The rear garage is missing from early aerial photographs

When the newsroom moved into a new south wing in the late 70s, maintenance techs took possession of that former front OB garage. They, too, were to vacate that precious vantage a decade later for, yes, telco racks for a fledgling Kooee/SPT.

And so it went.

Photographs of the Mosbri Crescent site reflect these changes, and since none of this collection was dated, one determines, like an archaeologist, the probable year by shrubbery growth and building extensions!

Why is it that shape?

Intrepid Novocastrians who wandered curious up Mosbri Crescent to behold Newcastle’s newest eyesore - sitting like an architectural sore thumb in the middle of a razed 3 acre paddock - were, in all likelihood, both mightily impressed yet completely puzzled by the shape and appearance of this “TV studio,” as the building’s inhabitants called it.

The original layout of NBN's Mosbri Crescent studio complex comprises the large box at left, Studio A, and the long box right, everything else - all the departments, including studio staging/props, aircon plant, engineering, Presentation, film processing, news room, sales, production, promotions, admin, accounts. It was busy in there. Reception is the extension at right.

The small box mid-front is a new OB garage, a convenient location but short-lived. It later served as a temporary news room, engineering staff's workshop, then filled with telco racks during the Soul Pattison Telecom era.

Mosbri Crescent was quite the wilderness back in the 1960s

That big box ugliness might have dominated the rapidly populating inner-city street, but the magic of the very idea of television quickly blinded both visitors and neighbours to the architectural transgression from which the magic of visual entertainment flowed.

Constructed like any huge shed in an industrial park, the steel frame was mounted on a vast concrete slab and then skinned with vertically profiled steel cladding.

Aerial view of newly built studio complex at 11-17 Mosbri Crescent, Newcastle. Landscaping has just begun, and a single vehicle is in the driveway! This must predate March 1962.

Broadcast studios require very low ambient background noise. The large box-like Studio A was fully exposed to the outside and needed a great amount of insulation in the walls and roof.

Broadcasting centres plan for low noise by a choice of location and an eye to future nearby developments. The generous 3 acres (1.2 hectares) of prime city real estate was to ensure airborne and impact noise would have to work hard to reach the sensitive microphones in the studios.

The trees and shrubs were a part of that strategy, and it also helped that they softened the boxy building’s look.

While a noise survey of the site might be undertaken to determine the quietest location to place the studio, the irony that the top of Mosbri Crescent was the focal point of a natural amphitheatre was probably not lost on the surveyor.

Above ~ A rare panorama - two combined photos taken from a crane (shadow lower right). The old logo still up and Arcadia Park is bare. But Mosbri seems fully populated. Date?

The ‘Studio’ Complex

To reiterate, the phrase “the studio” conjures up for most of us the idea of a recording or production studio, with lights, cameras, and microphones.

But the staff, rather than saying “NBN head office” or “NBN at Mosbri Crescent” or “the office/HQ/...,” the site in Newcastle was called simply “the studio.” Company operations, however, naturally referred to either Studio A in full, to be sure visitors and talent knew where they were required.

Just so you know. Now you’re an insider.

The first question all would ask, or at least wonder, is why there were no windows.

Rear (eastern side)of NBN Television studios in Mosbri Crescent viewed from the west. Circa 1970. No windows long the front... no noise please.

While some windows graced the building’s rear, and gave scenic inspiration to the general manager and board of directors, there was no need for outside views in operational areas. Even the general office - a large area on the first floor at the front, only had windows along the southern side.

Those windows nevertheless were double-glazed with adjustable blinds between the panes. All subsequent extensions in the late 1970s, when a new administration wing was added at the southern end, used similar sound-reducing windows.

Below, viewed from south west. The new OB garage is added to the front of the building, its roller door facing camera. Circa 1970.

Below: View from south east. A rare colour shot from that era ~ Circa 1970s. If you listen carefully, you might hear the colour-grading technician complain "Magenta in blacks!" The restful garden park would by 1980 be consumed by a southern wing to house an expanded news room and administrative offices.

Here, by the way, is inside that famous and very-1960s foyer. And how NBN's studio complex greeted visitors and staff during the first 15 years of operation. There was also an additional small foyer at the front of the building for visitors to Studio A to congregate.

In the picture above to the right of the receptionist is a zoned security/fire alarm system. Such extravagant measures were mandatory for broadcast facilities. Not so much for ‘terrorists’ but to more keep fanatics or pranksters from interrupting or, worse, commandeering a live transmission. For decades the station employed an on-site security guard. In latter years, security devolved to card-key accessed doors and a button under the receptionist's desk to sound a buzzer in the executive suite!

Above ~ Don't you miss wood-grain veneered plywood?

Inside the Studio

There are four types of television studios: general purpose; theatre type; interview and announcers; and dubbing suites.

Studios A and B were general purpose, but A was large enough to be converted to a theatre with the construction of temporary audience seating.

Studio A dimensions were modest by metropolitan standards but still impressive upon entering. It was 21 by 15 meters, and 10 meters high with a volume of over 3,000 cubic meters.

Studio A was a really big space. Its reception entry at right became the entire complex's foyer during the 1978 extensions that required demolishing the original foyer.

Above ~ Production in NBN Television's studio A. This vantage shows just how big a 10 meter high room is.

Lights can be lowered to floor level by winches visible in the picture below. Sound insulation (on internal walls) is contained by wire mesh.

That’s a shot (below) of floor manager, Ian Host, painting and wearing overalls. Ian worked for Film Australia later and died when he was quite young but I don't know under what circumstances. ~ Wendy Borcher

The actual canvas cyclorama (“cyc”) is not installed yet in the picture below. It will cover the walls and apear as a depthless grey background. Being painted grey, also, is a bevelled “ground row” that covers strip lighting and a multitude of sins, and will seamlessly match the grey floor with the cyc. Apparently it’s getting the first coat of what looks like clear sealant before becoming “non-chromatic” grey or perhaps it’s half-painted grey and that’s a posed shot using a clean new brush!

Floor manager Ian Host wears overalls to protect his standard issue white shirt, black trousers, and tie - them were the days. If any paint gets on those suede shoes he’ll get an earful from his Mum.

A cyclorama is a continuous background curving around corners to give the illusion of greater space or infinite distance. Lighting behind the ground row gives soft backlighting, and the “cyc” can be coloured by spot lights.

An entire (but small) orchestra fits easily into a corner of Studio A.

Ian Nash and Friends concert in 1975, the year colour launched but the show used the original RCA black & white cameras, one of their last big shows. Relatively small by metro standards, but NBN's Studio A certainly packed them in and got the job done.

Control rooms on the second floor fronted the southern wall of the studio, where it joined the other building. They overlooked proceedings through soundproofed double glazed windows. Beside the vision switching room was a clients’ viewing room, an audio switching room, and an announcer’s booth.

The vision switcher shown below, while more than adequate at the time, is laughably simple by today’s standard. It comprised essentially three rows of buttons, a preview row plus A and B program rows whereby selected inputs - camera, graphic, film - were switched or faded to.

The director and assistant in vision control for Studio A. The vision switcher is likely an RCA PTS-1 . It is indeed a spartan affair, but at the time seemed quite glamorous and 'high-tech.' Nevertheless, broadcast media was still in its steam age, with barely a transistor in the building, and 'digital' had entirely different connotations.

Shown at the vision switcher above is Bill Bowen, a former head cameraman. The producer’s assistant (PA) seated next to Bill has been identified thanks to Allan Black’s networking efforts...

that's my friend Antonia Salaris sitting next to Bill Bowen in the control room. Annie took my place as PA when I was transferred to the Newsroom in 1964.

~ Wendy Borcher

Above, just visible through the windows and 10 meters down are floor operations. A row of monitors (top left) preview camera vision. Another also shows outgoing vision from the studio.

The window glasses are not parallel to prevent vibrations on one resonating the other.

Meanwhile in the next room the audio operator selected the matching audio from microphones corresponding to cameras, telecine film, record turntables or tape, and, yes, the human announcer in his tiny booth doing live voice-overs.

Studio A floor as seen from the audio operator’s booth.

Here’s floor manager Len Richardson (above) sitting at the brand new Studio A RCA console, the day the power was first turned on in early 1962.

This was staged and shot by station photographer Des. Barry, who positioned announcer Laurie Burrows, production manager Matt Tapp and lighting director Barry Jones in the studio to add some life to his shot (so he told me over a drink later at the Delany Hotel).

~ Allan Black

Props Bay

Studio A‘s sliding door (below, at right) from the props bay was large enough for tall fully-constructed sets to be wheeled, and even trucks could enter (if they could manage the turn).

Studio A’s sliding door was a really big, solid, heavy door and I was always ready to run like the blazes should it make the wrong noise whilst being slid.

The very heavy sliding door was about 5 meters high and similarly wide, and about 10cm thick to block noise from the props bay.

The carpentry shop (for making studio sets) was in a mezzanine in the props bay, but the noise interfered with studio operations despite insulation so it was moved the rear garage.

Studio A - Not just a big room

Being a relatively small television complex, the larger exposed Studio A received noise on its external surface from all sources: vehicles, loud neighbours, storms, and passing aircraft.

The roofing material was corrugated asbestos, chosen to minimise noise from heavy rain and impede heat from the sun conducting to an interior already suffering heat load from studio lights.

A major challenge was designing air conditioning outlets of sufficient volume to counteract tens of kilowatts of heat from the lighting, and on scorching summer days the heating of the external metal walls and asbestos roofing - yet have an almost perfectly silent air flow. Circa 1965.

Interior walls were extensively insulated too, in addition to the ceiling, to reduce outside noise that would disturb, and possibly entirely disrupt, sensitive sound recording. Original architectural notes and engineer’s specifications for this studio would make interesting reading.

Studio B was a small internal room without configurable overhead lighting.

It grew out of the original operational space, and I’ve been unable to precisely establish if it existed from the start. A picture I recall - I think I recall! - showed Allan McGirvan operating a console in a control room that oversaw the space where Studio B was in later years. That console was referred to as ‘Presentation’ and later became Studio B’s control room.

Though rather cramped, its 40 square metre floor space was serviceable, however, and it served as a commercial production and news studio for several decades, and hosted Art Ryan’s Breakfast Club for its duration.

The roofing material was corrugated asbestos, chosen to minimise noise from heavy rain and impede heat from the sun conducting to an interior already suffering heat load from studio lights.

Interior walls were extensively insulated too, in addition to the ceiling, to reduce outside noise that would disturb, and possibly entirely disrupt, sensitive sound recording. I have yet to find construction details for this studio, but the architect’s notes would make interesting reading.

In Studio A the studio floor was made from an early version of Magnesite. This was a cork, rubber, sawdust and glue compound. It was laid specially for smooth tracking by the TV cameras. In early 1962 it was laid by specialists who carefully levelled it and waited about a week till it dried and set. But today there are serious problems ...

When I was there in July 2018, the Magnesite with an average life of 30years was breaking up and it‘s now covered with black plastic, which without lighting, makes the studio a dark and sad place.

~ Allan Black

Studios weren’t simply big rooms in isolation. They were supported by a series of control rooms: vision control, audio control, camera controls, announcer sound booths, lighting control, talent makeup rooms, even clients’ viewing room.

Access was through air-gapped rooms with dual sound proof doors.

Before leaving the studio, some respect to generations of lighting technicians who had the privilege of working from a cramped and cluttered "cage” in the props bay. Though by century’s turn (when photographed) accoutrements of modern times added to the chaos, it’s highly doubtful any item dating from 1962 ever departed this hallowed space. In other words, this is how it always looked.

Above ~ A lighting technician's work is never done.

News and Sport

From day one - well, hour one - news was NBN Channel 3’s flagship.

Above ~ In the hat, Bud Budden with cine cameraman Mike Leyland.

The guy in the ‘flat hat’ is Bud Budden. He was the 1962 NBN chief TV set designer and constructor and produced remarkable sets for all the live TV shows with minimum budgets. He also enjoyed working with 3 Cheers clown Norman Brown, and his hat is probably a throwback to his early days as a variety performer in theatres around Newcastle and districts.

~ Allan Black

Below ~ In hats, from mid-right, Norman Brown and Bud Budden, while Mike Leyland films for the news.

Less than surprising, then, is the list of well-known people who sat behind our regional TV station’s news desk.

Most of the early conscripts stayed. Noel Harrison, Murray Finlay, Des Hart, Neville Roberts, Neville Graham, Brian Newman, and Wal Morrison were entrenched as local celebrities.

Reporters and newsreaders became household names - Murray Masterton, Mary Boddy, Chris Ford, and Jim Sullivan.

The years were to bring more, too many to mention (forgive me), including Ray

Dineen, Anna Manzoney, Jodi Mackay, John Church, Nat Jeffery, Melinda Smith,

Art Ryan, Ian Hill, and the lovely Romper Room hostesses.

Meanwhile,

personalities like Darryl Eastlake, David Fordham, and Chris Bath, wended

their successful ways to the big smoke.

Mike Leyland, NBN's first news cameraman - or shall we say "cine-cameraman"?

News and sport delivered above their weight.

Over six decades, NBN News produced Good Morning News, Good Evening News, News Night, NBN Evening News, and NBN Late Edition News and the still running 6pm NBN News.

There were many specials and spinoffs, including royal visits, floods and fires, and notables such as The Cruel Sea, following the beaching of Pasha Bulka in 2007.

Above ~ Neville Graham at the Studio A news desk circa 1965. Everything was on wheels, including of course the cameras. That floor was dead flat, as you would guess from the miniscule clearance of the camera pedestals.

Above ~ It could be news, it could be a commercial shoot. The container simply said "NBN Colour Doco" but Barry Nancarrow thinks the most likely candidate is Stewart Osland, who became one of the legendary news camera team of the 70s and 80s.

Newcastle’s first, only, and last drive-though bank. It was a good idea until they noticed every customer was either a lazy bank robber or some fool ordering KFC. E.S.& A. Bank (English, Scottish, and Australian) became ANZ in 1970.

Below ~ Both this and above are of the same date.

Des Hart, NBN's inimitable weatherman (not to demean his eminent colleagues; as Des, in his humility, would have been the first to insist).

There are, without doubt, dozens of incidents shared with embarrassment by the staff. These are two.

Late news was set up with a fixed camera in Studio B and was unattended. The newsreader sat alone at the news desk and started reading on cue.

One night one of the floor crew and I (we should have known better) entered and were greeted by Murray Finlay’s booming “Good Evening.” Thinking he was just taking the mickey, we called back “Oh, howdy Muzza.” and “Yeah, gidday Fin!”

His response was to ignore us and start reading to the live camera the first story of the late night news. Oops! We tip-toed out and avoided eye contact for a week.

Unattended news bulletins had their risks but were a staffing necessity for early morning or late night bulletins. No degree of staffing could have avoided this incident…

I think it was early morning news from Studio B. One of the coolest NBN journos, David Allen, was rattling off the news headlines when the letter “e” fell off the carved wooden word “News” right behind him in frame. Everyone watching would have seen it happen.

It made quite a racket - it was a very big piece of wood.

Without flinching, and in his dulcet tone, Dave finished calling the headlines, then added his own breaking story… “and the letter ‘e’ falls out of News!”

Above ~ Jim Sullivan's Motorscope.

Below, Noel Harrison interviews a crew member of the famous racing yacht ‘Gretel.' The photo was labelled "Gretel crew" so assumedly not 'Gretel 2.' Anyone assist with the face?

The photo above is from a collection labelled "Sports Report" that it nevertheless might or might not be from. And the one below? Noel had a lot of shows that ran through the sixties into 70s and into colour. Trouble is, I never watched any sport shows, so... help, anyone? Email Throsby at NewcastleOnHunter dot org

Noel Harrison, NBN's sports editor, in the OB truck.

Program Production

One of the surprising aspects of NBN’s early decade is the amount of local production generated both within the studio and in the field.

Mike and Mal Leyland became household names, while Ian Hill and Art Ryan carved their names in program guides.

Then there was Greg Gomez Pead, seen below editing film by cutting out frames and splicing back together. Probably in the early 1970s. Around his feet the term “ended up on the cutting room floor” is clearly explained.

Greg’s gloves are to protect the film stock. His coat is for effect. And, yes, his face is familiar.

Romper Room was equal favourite with the station’s 6 o’clock news. NBN acquired the franchise from Fremantle International in 1967, and locally produced and broadcast the show for over three decades.

NBN's Romper Room celebrates its 5th birthday. Perhaps in 1972?

The original hostess was Miss Anne, then Miss Lyn, Miss Pauline, and finally Miss Kim, who hosted the program until 'political correctness' overtook it. As legend goes, a favourite feature called 'bounce-the-ball' was deemed inappropriate because not all children could bounce a ball.

Romper Room went into the field quite often. These were diligently recorded by the staff stills photographer but rarely warranted an outside broadcast recording. There is such a large collection of pictures that a separate article is planned, just to display the entire album.

Below is a Winns event in the early 70s. Romper Room at Winns Department Store circa 1973-ish.

Were you one of the Romper Room kids at Winns in the 70s? Let us know on in the comments section below, at the end of this article.

At first the Miss was assisted by NBN's station mascot Buttons the Cat, who underwent a number of incarnations as its costume aged.

Later, Buttons was retired, to be replaced by Humphrey B. Bear (as NBN had gained the rights to the character through their purchase of Southern Television Corporation aka NWS 9 in Adelaide).

Above ~ Concept art for Big Dog in 1982.

A Local suited character was then determined to be more suitable for a regional television station and in 1982 the concept of Big Dog was born. In 1983 NBN ran a live two-hour show The Early Birds to introduce Big Dog to his Newcastle audience.

Puppeteer Murray Baine has kindly offered some perspective. His photo below was taken on the set of The Early Birds, one he created and painted in late 1982. Murray left the show early in 1985 to work as principle puppeteer for The Marionette Theatre of Australia. He now operates Murray Raine Puppets (YouTube link).

When I auditioned for the show, Big Dog was just a concept, the costume not yet built, and it was still Humphrey B Bear. So I did my audition with Humphrey pretending he was a dog .

The Early Birds show proved a great success and so did Big Dog. We went live each weekday morning - 2 hours, no rehearsal and no script. The cast was Miss Kelly (Kim Austin*), myself as Professor I. Bungle, and Big Dog which was played by Terry Lewis, the NBN photographer! The director was Rob Short.

From memory we did about 2 years of The Early Birds and during this time Big Dog And Friends show was produced. Again this was 2 hours of live un-scripted, un-rehearsed television every Saturday morning. During 1984 we went to recording the show on Friday afternoons which was a lot less stressful.

Kelly, Professor Bungle, and Big Dog in 1983. Photographer Terry Lewis. Image supplied by Murray.

*Kim Austin is alternately recalled as “Kim O’Brian” so we’ll leave that open until the real Kim let’s us all know. Anyway, we’re too far in the future. Lots more in an upcoming photo essay centered on Romper Room and that dog.

Above ~ Romper Room in Studio A. Before colour - the cameras are the

original monochrome RCA TK-60s. In the crew was Barry Nancarrow who

thankfully has named the lads, from left: Russell Phemister, Rod Margetts,

himself on boom mic, Roger Bliss, and Phil Lloyd.

The NBN edition continued after the station became an affiliate of the Nine Network, with a new title, Big Dog and Friends in 1997, the title referring to the station's mascot Big Dog, who appeared in the show as the sidekick of the hostess, Miss Kim (Kim Anthony).

This was renamed due to NBN's rights with Claster Television for using the "Romper Room" name, songs and characters expiring in the end of 1996.

The last series of Romper Room to survive on Australian television was cancelled in 1999 after Kim Anthony retired from hosting the show.

Below ~ NBN’s four Romper Room Miss' with director Reg Davis on the set in Studio A for its 20th birthday.

During that first decade there were dozens of local programs from the studio.

Jayes Travel Time started in 1962 and ran for 20 years. Telethons every four years were quite amazing events that cemented community spirit as no other television program could.

Bob Dyer’s BP Pick-a-Box became an instant favourite, though a national show. Locally, however, NBN’s first shows were Ken Eady’s Home At 3, Allan Lappan’s Tempo, Murray Finlay’s The Three Cheers Show, and Cyril Renwick’s Focus.

Neville Roberts unable to maintain composure as outrageous British actor and comic Frankie Howerd dominates.

Barry Humphries and The Bee Gees were early talent in the old studio, as wonderfully related by eye witness and original staffer, Allan Black.

Next is a potpourri of just a few of the many things that went down in that fabulous old studio - some well known, some forgettable, and not to overlook the endless advertorial shows or commercial production that paid the bills to let us enjoy “free-to-air” TV.

Above ~ 1970 schools choir in Studio A.

Below ~ Selection of unknown, if not unknowable studio events.

Above ~ Lionel Doolan from Newcastle Technical College demonstrates how to convert electronic components to smoke. Or is that someone’s cigarette?

Above ~ were you there? Let us know in the comments, so that this story can be expanded. Also mention if you still have your white knee-length socks :0)

Catherine let us know that this was "NBN's 10th birthday party in 1972. All the kids in these party photos are from the 4 March 1962 Club - born on the day of NBN's first broadcast - and I'm one of them."

Below ~ This charming string of photos tells a story. It says that kids can't party on demand and would rather know how all this television stuff works. They're also discovering that in front of the camera is not as glamorous as they imagined. And the floor manager, director (wrangler, handler?) is trying to figure out why the talent won't comply.

Below ~ Ian Nash and Friends in 1975. The cameras are still RCA monochrome originals, although the colour equipment was commissioned by now.

Above ~ Always great - and all too rare - to find paperwork! Those nagging “who, where, when” questions answered beyond doubt.

NBN attracted not only many of the region’s most enthusiastic and capable people to express their passion for television by working behind the scenes. It naturally placed before the viewers the most capable talent.

Of the many greats that faced the studio’s cameras across the years, Neville Roberts was legendary. Except I can’t find anything to say about him. Fortunately his frequent capture on celluloid says much and answers some questions. But a brief bio is deserved here, so if you can assist you're welcome to add all you can in the comments to this article.

Within a decade of its inception, NBN3 was producing quite lavish productions in its modest regional studio. Here Tonight’s multi-year run spared, as they say, no expense. These highlights are from 9th March 1971.

Little Pattie aka Thelma Thompson interviewed above and singing on set below.

Above ~ This is the “no expense spared” referred to, and for a regional station as relatively small as Newcastle’s NBN, quite impressive.

The extras patiently await instructions. That small mark on the floor is tape

to mark the pre-lit hot spot for talent to know where to stand.

Reminder: All are welcome to contribute with additions and

corrections to this “living” document.

I couldn’t place the personality Neville was interviewing below, but was gently reminded by Andrew Bayley that it’s our old friend Winnie. You, too, can contribute additions or corrections by email to Throsby at NewcastleOnHunter dot org

Below ~ Neville interviews Winifred Atwell, a household name of the sixties, known and loved for her upbeat piano works.

Tours

Although there’s nothing special in these few photos (unless you recognise a younger self) their value lies in the early studio innards that are revealed.

The following shows a view rarely photographed from within Studio A, where its southern wall joins the other building. On the second floor through the windows at top left are the control rooms and booth with an access stair case at right offering direct access to the floor.

A 5 metre ladder at left is used by lighting techs to change blown lamps and sundry tasks. Center-left behind the guy standing at rear are double doors into Studio A’s public foyer, that opens to Mosbri Crescent.

The plastic chairs are rented.

The group of lads in these pictures are - judging by their safari suits,

knee-high white socks, Bermuda shorts, and world-weary expressions - field

television service techies having a Captain Cook at the studio during its

preparation for colour. Or not.

Internal spaces were progressively

torn apart and reworked on both floors over the decades.

The following photos could be anywhere, though I suspect it’s a future Studio B control room. The desk and equipment are for audio control. Studio A’s audio control was not this large, as I recall.

Foreground below is a Plessey CT80 audio cartridge player (left) and a Rola 7-inch reel to reel audio tape deck - cooled, not unusually, by a small desk fan!

That was no novelty. Back then the electronics were full of vacuum tubes (valves), thousands of them throughout the studio, each as hot as a small incandescent light bulb. There was always a handy giant pedestal fan to blow at any hot spots.

The group patiently waits while the photographer lights up their retinas with his sunlamp and fiddles camera exposure.

Below ~ Rola 77 tape machine at left. These Australian-made decks were ubiquitous industry workhorses throughout the 1960s, 70s, and well into the 80s. The audio mixer at center is an RCA BC-6.

Above ~ How the RCA BC-6 audio mixer looked to an excited operator back in the day, when it was installed in 1962. Image credit Reverb.com

Below ~ Clearly uninspired even by John Kidd's silver tongue, the entourage is on the ground floor in what would soon be refitted as a colour master control room - a nerve center where all sources converge before leaving the studio, bound for the transmitter.

The ground floor was riddled with trenches called cable ducts covered with removable steel plating.

I have a story (from a friend, a credible source) about an early technician (whom I also know but chose not to embarrass by seeking confirmation). He left a tap running in the Studio B sink. The drain hole was partially blocked and it inevitably overflowed.

Cable ducts were filled with water. They’re packed with a mix of cabling carrying all sorts of audio, video, and camera cables, many with quite high voltages. Apparently nothing stopped working but it took weeks to dry out the ducts.

He bore the title “The Harbourmaster” for a few years."

And so to “Engineering”

You didn’t really think you’d escape the machinations of the engine room, surely?

Engineering was always a slightly grandiose term, like steam engine drivers were termed ‘engineers.’

But it was appropriate because while technical staffers rarely had engineering degrees, they were the best and brightest of can-do techie smarts you’ll ever find in one place.

While electronic, electrical, and mechanical engineers and scientists in corporate research designed and built (not always very well) the vast array of intricate broadcast equipment, it was NBN’s technicians who kept this horrendously complex and disparate collection of enigmatic, often poorly documented, and frequently delinquent gear working.

Continuously, daily, yearly, with many a-brush with catastrophe that you rarely saw on your TV at home.

Some background.

When 2KO’s owner, John Lamb, bought Sydney radio station 2UE in 1954, he established a formidable conglomerate to lobby for television licences. 2UE was one of a group of commercial media and electronics organisations pressing the Commonwealth government for a Sydney commercial TV station licence.

Over the next decade, as the government ‘loosened up’ on the issue, it was clear that Newcastle could have a commercial station, and Lamb turned his attention there. A consortium of locals (NBTC) formed in 1958 got their licence 3 years later and the race was on to create a television station in a year.

Staff were hired, tempted, coerced, or shanghaied from all over, but primarily

it was 2KO and 2UE staffers who were seconded to the massive undertaking.

Staff were hired, tempted, coerced, or shanghaied from all over, but primarily

it was 2KO and 2UE staffers who were seconded to the massive undertaking.

2KO’s chief engineer was Ken Greenhalgh, who had been with the station from the early days when Sir Allan Fairhall realised the full potential of his backyard hobby.

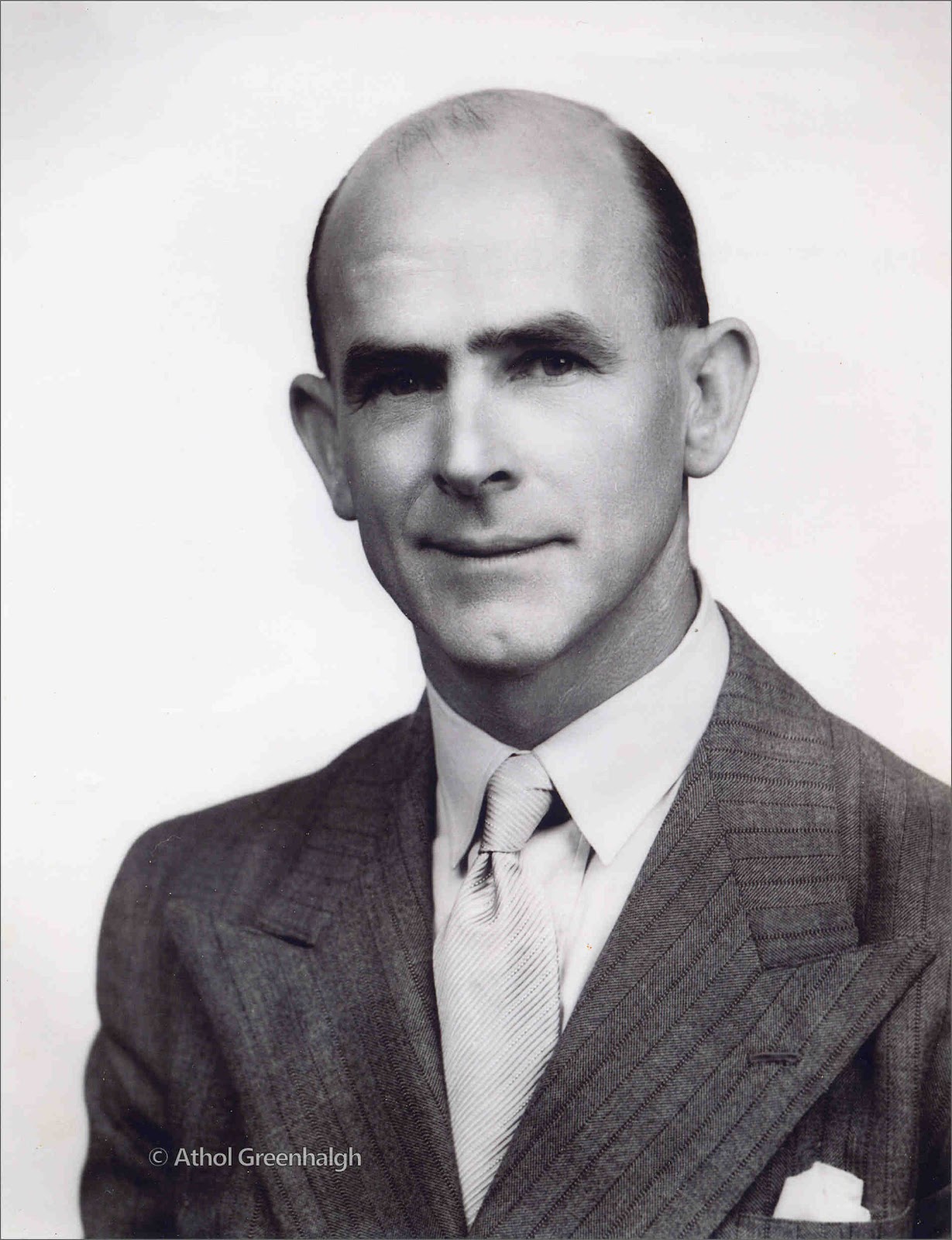

Here’s Ken Greenhalgh, the first NBN chief engineer in 1962. Ken and his crew worked a remarkable engineering schedule to get Channel 3 on air, on time 6pm 4th March 1962.

~ Allan Black

Ken became NBN’s first chief engineer for the project’s duration, after which his deputy, Harry McPhee, would take that role.

Even before the mind-bending complexity of digital broadcasting, radio was a tricky artform of manipulating waveforms from mouth to voltage to radiation and back to sound waves in the listener’s ear. Adding pictures took it to a whole new level for the engineers and technicians of the sixties.

Ken Greenhalgh (above) couldn’t wait to learn on the fly after RCA’s equipment arrived so he went to Hawaii to wrap his brain around a working television station, KULA-TV in Honolulu. Image supplied by Allan Black.

Above ~ Jeff Beach testing one of NBN’s RCA TRT-1B videotape recorders. The station first aired with just one and the second arrived soon after.

Every new item of television equipment ever purchased in the history of the industry arrived fresh from the factory hiding a multitude of design and operational sins that drove many technicians to an early grave. Literally, in those days when heavy smoking and drinking were a social norm.

In the beginning there was a dedicated videotape technician, Keith Campbell. He was let go with about 80 others after about 18 months, and Chief Engineer Ken Greenhalgh returned to 2KO when the Lamb Family departed, so his job fell to Harry McPhee (NBN’s first Assistant Chief Engineer, then Chief).

Behind all of the corporate shenanigans Harry worked himself to death spending long hours on complex problems - particularly with transmitter issues, and the finicky TRT-1B RCA videotape recorders.

~ George Brown

The issues referred to were to not only because equipment was vacuum-tube-based (and tubes wear out as light bulbs do ~ inevitably and randomly), or that it was complex and new and full of teething problems typical of new equipment, but particularly because it was retrograded obsolete monochrome broadcast equipment from America, where “color” had been operational for a decade.

Future Assistant Chief Engineer, Max Lewis, works on the tape transport of an RCA TRT-1B video recorder. Also pictured, Joe Brown, future OB Supervisor.

On top of it all, the U.S. used a different system to Australia, so the RCA engineers not only had to revive old designs, but convert them to a different engineering standard (525/60 vs 625/50).

NBN's first videotape machine, the RCA TRT-1B “Television Tape” recorder. Circa 1963.

Some of my fondest memories... Forgetting to drain the condensed water from the head wheel compressor, and halfway through a playback, having water begin spitting out of the head... putting a new head on a machine, recording a 90-minute show, and finding the head completely worn out due to a piece of "green" tape... fixing the many, many, relays, by soldering a piece of copper braid across a broken hinge.

~ From VOldBoys

These monsters cost some serious money back in the sixties.

The TRT-1 occupied up to six equipment racks. The transport unit occupied three 84 inch racks, with the transport mounted vertically in the center rack. It weighed in at 1,450 pounds. Six power circuits were required to run the machine totalling 4.65 kW! Several of these beasts are still in existence, including one in a museum in Perth, Australia.

~ Tim Stoffel

The staff photographer in the day had a tough job. While studio lighting was complex and TV cameras more so, at least feedback was instant in the viewfinder. But a stills photographer had know his stuff (depth of field, film speed, exposure) because proof of decisions about exposure and focus were ultimately only in the developed negative - rather too late to adjust fine details.

With that in mind, it’s interesting to examine (the original of) a photograph that appeared in the NBN booklet “Your Guide to NBN Channel 3”.

This promotional photograph of new Ampex colour 2-inch tape machines (VR-2000) shows the original surviving RCA TRT machine at left operated by Lyn. Jeff Beach is at the controls of the Ampex machine. Clearly visible behind him is an RCA TR-50 high-band colour recorder, which shows just how much money NBN was pouring into this technology. A working demonstration video of its successor, TR-60, is on YouTube, here.

From this we can see our photographer was forced to retreat into the corridor and photograph through the window. If you’ve ever tried that, you’ll know all about reflections. Placing the lens against the glass can reduce reflections but then not much distance from the subject is gained. The window sills are visible so he (or she) was standing well back.

His fixed lens just wasn’t wide enough.

A section of the image above was scanned at 3200 high-resolution to clearly reveal 'Dusty Springfield' tending to the RCA recorder. In foreground is a Tektronix oscilloscope - probably a 545 or thereabouts model.

Above ~ A section of the previous photograph scanned at 3200 dpi shows a rarely seen angle of operations in 60’s VTR.

Outside Broadcasts (OBs)

Also known as "outside telecast" and "remote broadcast studio."

A foreword before we begin. Studio technicians had their many problems to solve, but the real “thrill seekers” were OB technicians who had to drive a mobile studio sometimes hundreds of kilometers to a remote location, cable it up, fix the unexpected faults and failures with few backup systems and fewer resources, all on an impossibly tight deadline.

They had to carry heavy cameras weighing 100 or more kilograms to the top of some building, or scaffolding they built themselves, and then work in blazing heat or pouring rain with high-voltage but delicate equipment connected to hundreds of meters of thick cable.

Just saying. These guys were real heroes.

That camera head weighs around 130Kgs. Although documents don’t specify if that includes the lens, with or without it's still heavier than a person. Have you ever carried a weighty object up an extension ladder changing rungs with your only free hand??

There’s little information here but many pictures of NBN's early days in the field, from which time few of the crew are known by the author, and the story is rather vague, too. A few facts have filtered across the decades, plus an amusing event or two.

Initially NBN had no outside broadcast (OB) department, nor a vehicle. One was acquired, I'm reliably informed, from Brisbane. Not so reliably, it was from either 7 or 9.

Quite likely this is the day NBN’s first Outside Broadcast (OB) van arrived. A garage would soon be added to the front of the building.

Below ~ Chief Engineer Harry McPhee (right) and Assistant Chief Rodney Prout with the OB truck and one of its TK-31 cameras.

The van came with a trailer of equipment, two RCA TK-31 black and white cameras, and at the time no recording equipment. Program from the vehicle had to reach the studio via microwave link.

NBN's first solid state video tape recorder was an RCA machine that was colour capable and could edit. This unit could also be moved into the OB van and thus do away with mobile microwave units.

This rare colour print shows the van and its microwave antenna. And, yes, 3's a crowd.

The old beast was a Ford V8 van with an American-built body 8 meters long, 2.6 meters wide, and almost 4 meters high.

Towards the end of its life, maintenance was a growing problem. On one sad occasion it was towed to the heavy vehicle motor registry at Carrington for inspection and re-registration. Never heard back what the inspector thought of that. But it was soon on the road again. Must have been awaiting a spare part from the U.S. !

OB vans are complete control rooms for vision and sound control and switching, with electronics racks and air conditioning. The only functional difference between it and the Mosbri Crescent studio is that the actual studio floor happens to be the real outside world.

For the first thirty years or so there was hardly an event of any significance that failed to attract a visit by NBN's OB unit.

Following are some random collections that show what difficult work it was, requiring planning and a wide range of skills. While types of events obvious, dates and locations not so - except the dockyard ship launch.

However, these photographs generically represent most of the typical outside broadcasts.

Bathurst 500

In the long history of NBN's OB team, there are few places in Australia they

haven't been. So Bathurst was just down the road.

Above ~ The cameras are brim full of vacuum tubes, each with its own little red-hot heater. Hence the sunroof.

Below ~ An email to Throsby reports an NBN staffer places this caravan of OBs at Merewether Golf Course, and the Bathurst pictures above are at Forest Elbow, apparently NBN's favourite picnic spot. Thanks guys for the info.

Many more OB photos to share in a future article. So much to do. So little time.

State Dockyard

Can you imagine the crowds a ship launching would attract today? At the harbourside crowds would be standing ten deep.

Below ~ The OB crew alights at the Newcastle State Dockyard to set up for the launching of the Australian Trader on 17th February 1969.

Above ~ Another of the many famous vessels launched at Newcastle.

Football

Rain and high-voltages, the perfect mix. We did OBs in the wet and, hey, on occasions gave TCN9 a hand, as they seemed a little unsure what these OB things were all about :0)

Below ~ An event of the Australian Rodeo Championships. While these negatives have no documentation, Gloucester is an informed veteran’s update.

A sign on the rear window reads “Get the highlights of the Australian Rodeo Championships .Sunday 24th November at 4:30pm NBN Channel 3”

Well, that's the short tour of NBN's early days in outside broadcast. Just another day in the OB department. Now, on to the next job. G’day mate, fill 'er up.

Good times...

The new T-shirts are here and I'm gonna wear mine everywhere.

And they did...

Below ~ Promotional photograph of the colour news set. Murray Finlay with journo John Lloyd-Green at the desk, and a new EMI colour camera at right.

The vibrant image above represents the ultimate destination of those early pioneering years. It well epitomises the change technology wrought on both the product and the people. From those incipient days of 1962 grew a professional team that would undertake the transition to colour broadcasting in its stride.

Despite the author's familiarity with both modern technology and old-school equipment, it’s still rather astonishing that almost every operation seen in this album of memories has been replaced by technologies that, with rare exceptions, are simulated by computer. That almost all the jobs shown in this photo essay are now computer keyboard operations, and that all the varied and arcane physical media shown have devolved to the ubiquitous computer file.

And in those heady days - as modern solid state electronics emerged from an electro-mechanical era of relays and vacuum tubes - our everyday flat screen television sets, mobile phones, and that amazing Internet, were futuristic science fiction.

All things considered, despite television having a generally “bad press,” we can agree that NBN’s version of it made Newcastle and the Hunter region a better place.

No, I don't still have the long white socks, but I do remember my mum getting a two-piece outfit made for me to go to NBN's 10th birthday party in 1972. All the kids in these party photos are from the 4 March 1962 club - born on the day of NBN's first broadcast - and I'm one of them.

ReplyDeleteThanks Catherine. That's really great information, and I'll add the date to the caption above. You're the first comment on this site since I reopened comments to everyone. Before, many people in the industry emailed me with corrections and additional facts that are now incorporated above, but email is the long way around. Comments are more immediate and I'm glad someone has taken the opportunity. Btw, you're quite welcome to describe your experience in more detail in this space.

ReplyDeletePS: Sorry about the socks 😀 I still have my cub scout top with all its badges from 1957 when I was ten! Tiny thing.

Post a Comment

Additional information, anecdotes, etc., or corrections are welcome.