It’s 1970. Colour television is coming and Newcastle’s Channel 3 has a lot of work to do.

Viewers are impatient. After all, Baird demonstrated colour in 1940 (as my Scottish neighbour regularly reminds me), the Yanks were watching "color" in 1953, and Europeans had enjoyed it since 1961.

Colour fever was fuelled by an industry convinced that viewers would again succumb to novelty and watch even the commercials with fanatical regard. Not an entirely flawed notion.

And so NBN3 set about building a new colour television station alongside an operating black and white one.

This photo essay looks behind the scenes as the Hunter region’s Channel3 prepared for the biggest technical and operational challenge since its inception 13 years earlier.

The images tell the story.

Feedback and CreditsAdditions or corrections are invited via email to Throsby at NewcastleOnHunter dot org Anecdotes and educated guesswork fill out the story. But it was, after all, a lifetime ago. This “living document” is informed by former NBN staff and anyone is welcome to contribute. Early photographs are credited to Des Barry, and later ones to Stewart Osland and Lloyd Hissey, NBN’s stills photographers during this period. Others might also deserve credit. Let us know. |

Below ~ NBN's touring “colour bus” that roamed the region telling one and all to buy a colour TV set - as if anyone needed reminding.

While it's painfully ironic that the only pictures of the bus in this collection are... monochrome, a reasonable explanation is that both colour and mono were taken, the colour negatives never returned to the archive. However, Robert Nimmo over at Facebook's The Memory Window has most kindly done the hard work for me, with this derivative work:

Nice one, Rob! I can almost smell the tyre black.

Choosing a Standard

Before indulging this album of memories, some technical background for the nerds.

Colour television in Australia was pencilled in for 1972, but as experts mulled which overseas system to choose, the date firmed up for 1st March, 1975.

One version has it that while most commercial stations had all the gear installed to broadcast in colour in the early seventies (some were experimenting back in the sixties) the ABC were dragging their feet, no doubt due to the extent of their network. So the Broadcasting Control Board, in their wisdom, decreed that commercial stations were not allowed to begin colour transmissions until March 1975.

The 10 network in Sydney were trialling colour for years before 1975. They had Rank Cintel telecine machines fully operational in colour.

Channel 7 had been broadcasting English video tape programmes in colour since 1970. Their machines were not optimised, but they had one employee (Victor Barker) who had worked for the BBC in the late 60s, so he knew all about optimising 1" videotape machines for PAL colour.”

BBC’s standard “test card F” adopted by NBN for testing its new PAL colour program path.

System choice was between European “PAL” (Phase Alternating Line) and the American NTSC (National Television Standard Committee). A third, SECAM, was never a serious contender. PAL had greater colour stability and higher resolution but required slightly more bandwidth for each TV channel. With U.S. equipment and television sets cheap and ready, many industry lobbyist would have been pressuring the government for NTSC.

Fortunately the PAL lobby had no trouble convincing Australians that NTSC stood for “never the same colour” due to a tendency to get the hue arse-about with little provocation.

Converting all of NBN’s operations to colour was a task so overwhelming in scope it seemed more difficult than the original 1963 project of building a station from scratch.

Below ~ NBN studio viewed northwards, circa 1970. The aerial view shows at lower-right a two-level extension that housed the new colour film department on the ground floor and staff expansion above.

Despite a challenge of starting with a concrete slab and a dream, the original installation was nevertheless “turn-key” from RCA who supplied cameras, mixers, links, transmitters, videotape, telecine plus direction by their engineers.

The first problem was how to construct the colour broadcast path whilst maintaining the existing monochrome operations. That would require a great deal of equipment relocation and making new spaces on the fully-occupied and very limited ground floor technical areas.

Colour conversion promised to be a piecemeal affair, bearing the additional challenge of choosing from a vast array of new colour technology with great aforethought, no experience, and everyone whispering in your ear what was the best brand.

Sales engineers flocking around the countryside promising their gear alone could do the task was no help at all. Manufacturers and vendors were queued at the doors of TV stations in the early 70s trying to edge out competitors in a lucrative sales opportunity to supply an entire country with colour broadcast equipment.

Eventually the big-ticket items were chosen: EMI studio cameras, Ampex videotape machines, Rank Cintel telecine, Grass Valley, Richmond Hill Labs studio desks, and a Filmlab colour processor. And a heck of a lot of overpriced colour vision monitors (TV sets without the tuner).

Meanwhile, in the real world

Out in retail land, electronics retailers and their customers, the viewers, were facing a similar dilemma - and to them, equally relatively expensive.

European PAL TV sets were stodgy, weird, and expensive and domestic field technicians were more than apprehensive about working from circuits written in German.

The only part on the circuit diagram we were sure of (colour circuits were vastly more complex) was the line output stage that the Germans obligingly termed “endstufen.”

There were all sorts of bizarre European TVs in the homes of wealthier folk who had jumped the gun in anticipation of NBN going colour. Retailers around town went mad, stocking anything that said “PAL” whatever the manufacture. I recall Nordmende and Telefunken sets. Sometime in the 70s the HMV/Thorn company stopped making sets in Australia and starting importing "Mitsubishi" innards from Japan. They put their "HMV" or "Thorn" brand on those.

Japanese TVs were a welcome mix of common sense design and reliability. Local rental firm O’Donnell Griffin went with brands National and Rank Arena, while Visionhire chose Philips. The cost of colour sets in those days meant rental was for many the only affordable choice.

But, despite jumping the gun in fond hopes of seeing colour burst forth in their livingrooms, these lucky folk saw but shades of grey.

In those officially pre-colour days of the early 70s, three things stopped the general public from watching the colour transmissions from the Sydney stations, and from NBN. The first was the fact that colour TVs were really hard to get unless you imported them at great expense - before local retailers decided which way the market was tending.

The second was technical. Video handling equipment throughout the program path were designed for black and white waveforms.

In the television waveform, line clamp pulses occurred on the back porch of each horizontal sync pulse (right where the 10 cycle colour burst would be placed for colour). This meant that the burst was effectively erased, and even though there was still colour information contained in each line, colour TV sets needed the missing colour burst signal to fully reconstitute the picture.

The third reason was officialdom. The Australian Broadcasting Control Board (ABCB) decided that having chroma content (more precisely, its key component, the "colour burst") was too much to allow to be broadcast before the official date and ordered stations to insert a filter to block the burst.

Hacking Colour

The ABCB provided a circuit diagram for stations to construct a filter. It comprised several passive stages, providing a fairly sharp phase-corrected notch at 4.43 MHz, with an attenuation of 20 decibels. This introduced a distortion into each station's output which contradicted the tight standards they were supposed to adhere to (flat video response, proper gamma).

Below ~Two horizontal lines of the old PAL analogue television picture shown on a waveform monitor. One TV line is a slice of the TV screen from left to right. PAL made a picture out of 625 of those lines, zig-zagging down the screen faster than the eye could perceive. Below is what a colour bars picture would display. The Colour “burst” is a blip of 10 cycles at the far left of the waveform.

A bright young technician studying colour television at Newcastle Technical college at this time astounded his teachers and class by displaying colour on the classroom receiver.

NBN television thoughtfully provided a sweep signal in one line of the vertical interval, which when strobed out provided a good view of the effects of the notch filter, and made it easy to set up my notch reversing circuit by adjusting stage gain and feedback to shape the reverse notch.

Of course, there was still no burst, but my remote control box with two push switches and a pot to optimise chroma frequency supplied that locally. In that was a burst generating circuit for generating gating pulses and locking an oscillator to the “chroma lock” circuit, then inserting the proper 10 cycle burst into the back porch of the line sync pulse. I also had to construct a separate oscillator to switch the burst phase line by line. It turned into quite a monster, but it worked.

I carted the whole lot over to tech college one night for the practical session of the colour TV servicing course and was able to show colour programmes off air from NBN on the lab’s own Philips K9 TV (which had previously only displayed colour bars).

Of course I had to have a tuner as well to feed my circuit board. I eventually sold that receiver to NBN and they used it for many years at Somersby to receive channel 9 for emergency relay into the link to Sugarloaf.

And that, for your reading pleasure, is perhaps the only documented case of remotely hacking a PAL colour television station.

Promoting Colour ~ The First Task

It’s ironic that so many of NBN’s photographs of this stage are not in colour, considering it was both the modern era of photography and subject matter was, you know, colour television!

Stranger still, the only photographs of the promotional touring “colour bus” are all monochrome. Certainly (surely) there were colour photos, but none were available for this article.

Branding for colour employed the original white logo, sometimes recoloured with the primaries red, green, and blue, as seen on technicians’ overalls further below. The logo sat over a straight rainbow background. Both news and OB vehicles bore the design, as did the studio and OB unit new colour cameras.

At the Newcastle Show

As roadshows must, NBN took to the streets with that bus. And where else to promote colour - other than retailers' shop windows - than at the universally-attended Newcastle Show at Broadmeadow.

Disclaimer: Showbags did not contain a sample TV sets.

Crowd pours in for NBN's Newcastle Show colour demonstration circa 1974

Below ~ Neville Roberts was the trusted face of NBN

Above ~ Neville explains the intricacies of colour TV.

Below ~ Nev's work is done. But She Who Must Be Obeyed is off to S&W Millers (or Churchills, or Retravision) to choose her TV set, whie He Who Must Obey is pondering with dread the price tag.

Choosing and Procuring Equipment ~ The Ikegami Roadshow

This series of photos is typical of those times. At first it seemed a tedious collection of unknown faces, but a review found it impossible reject any. Therefore, what follows is far too many photos of a single event. Yet, aren’t too many pictures never enough?

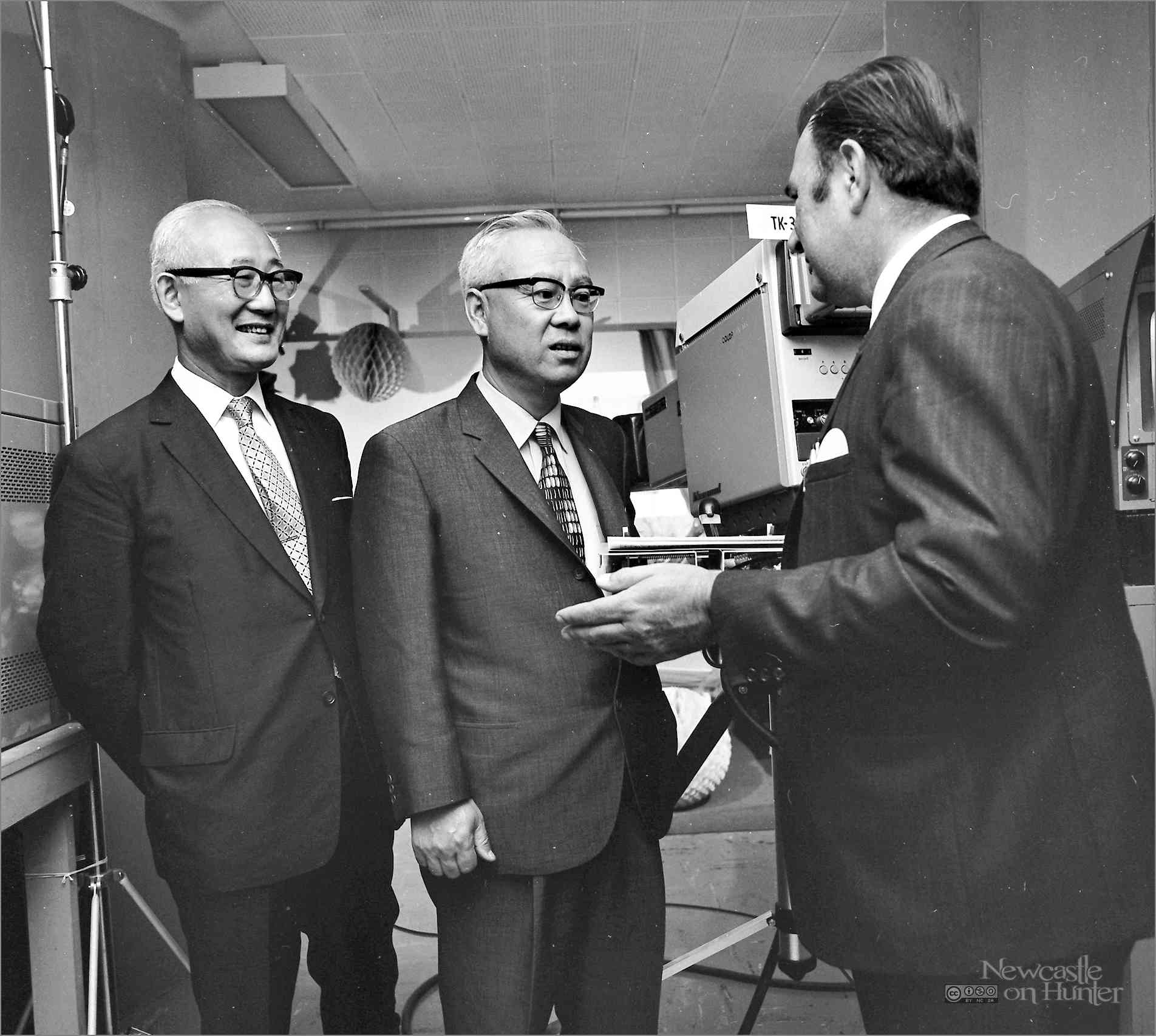

Ikegami’s range of colour equipment was demonstrated at NBN in the early 1970s. Ikegami never managed to sell NBN any big-ticket items. British and American firms got the contracts.

Above, from left, TGK-9TC caption scanner, TM-1B colour monitor, and TK-305 colour camera.

Above ~ Far right, on the floor in a glass case... a geisha doll?

Below ~ Charismatic Chief Engineer, Harry McPhee, with Ikegami Japan representatives.

Above ~ Is Harry’s broad strine, or that he tried a Japanese phrase and bombed? Or did they just learn what NBN's colour budget will allow?

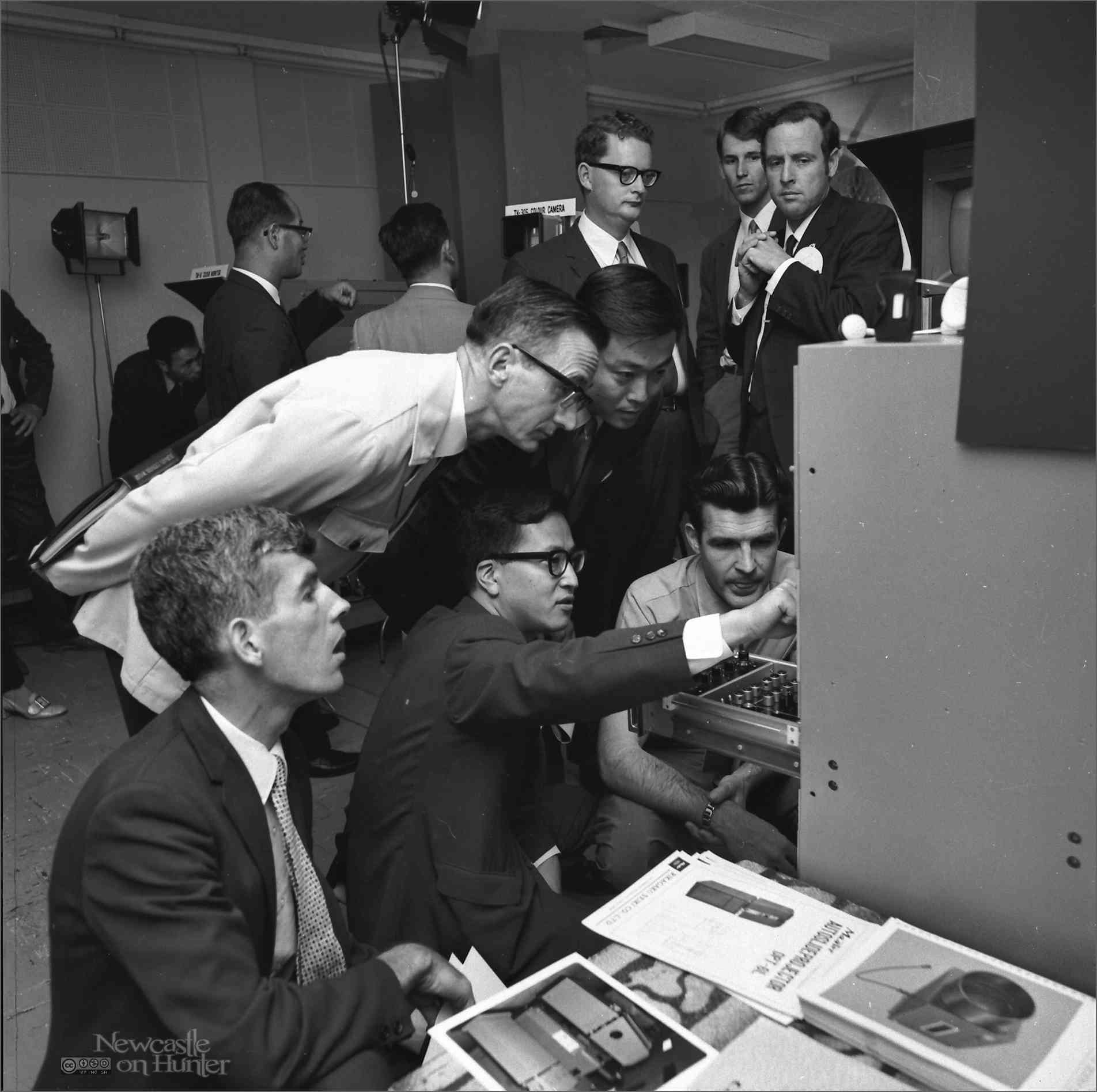

When sales engineers unpacked their exotic array of gear, it wasn’t only technical staff taking an interest. Anyone who could crowded into a demonstration. The crowd were not all NBN staffers. Judging by the assembly it was an NBN-hosted “show and tell” for the city’s VIPs and media representatives.

Below, center ~ The Newcastle Sun’s Matt Hayes

Above ~ The look and feel of this gathering is, it’s a mix of local industry leaders and media. As always, if a reader can identify anyone pictured, or has some related information, kindly add a comment at the end of this article.

Above ~ An overly-enthusiastic crowd finds Studio Supervisor Merv Hardy at far left, with VTR's Jeff Beach in front of him.

Below ~ Hmm, what dark magic is this?

Above ~ オーストラリアは美しい国です。 すべてのカラー機器を購入する必要があります

Oh, umm, it's about 3 o'clock.

Below ~ Remembering Robert Brown and his insatiable curiosity.

Below ~ Rod Prout, Assistant Chief Engineer (far right) and Max Lewis (spectacled) keep a serious eye on proceedings.

EMI Cameras

A prominent factor in NBN’s choice of EMI 2005 colour cameras was their superior rendition of skin tones, something manufacturers at the time still found hard to get right, especially under all lighting conditions.

That might sound like an opinion in the face of hard science and rigorous PAL specifications. But it was regularly witnessed during the early years in pictures from demonstration cameras of various manufacture, and in incoming vision from other networks and consistently revealed by a consensus of precision studio colour monitors at NBN.

A likely explanation was that every manufacturer had their own method of implementing that standard, and were subject to their engineers’ choice of colour camera tubes, coupled with the ultimate challenge: deciding what was the actual “colour” of skin. And whose skin?

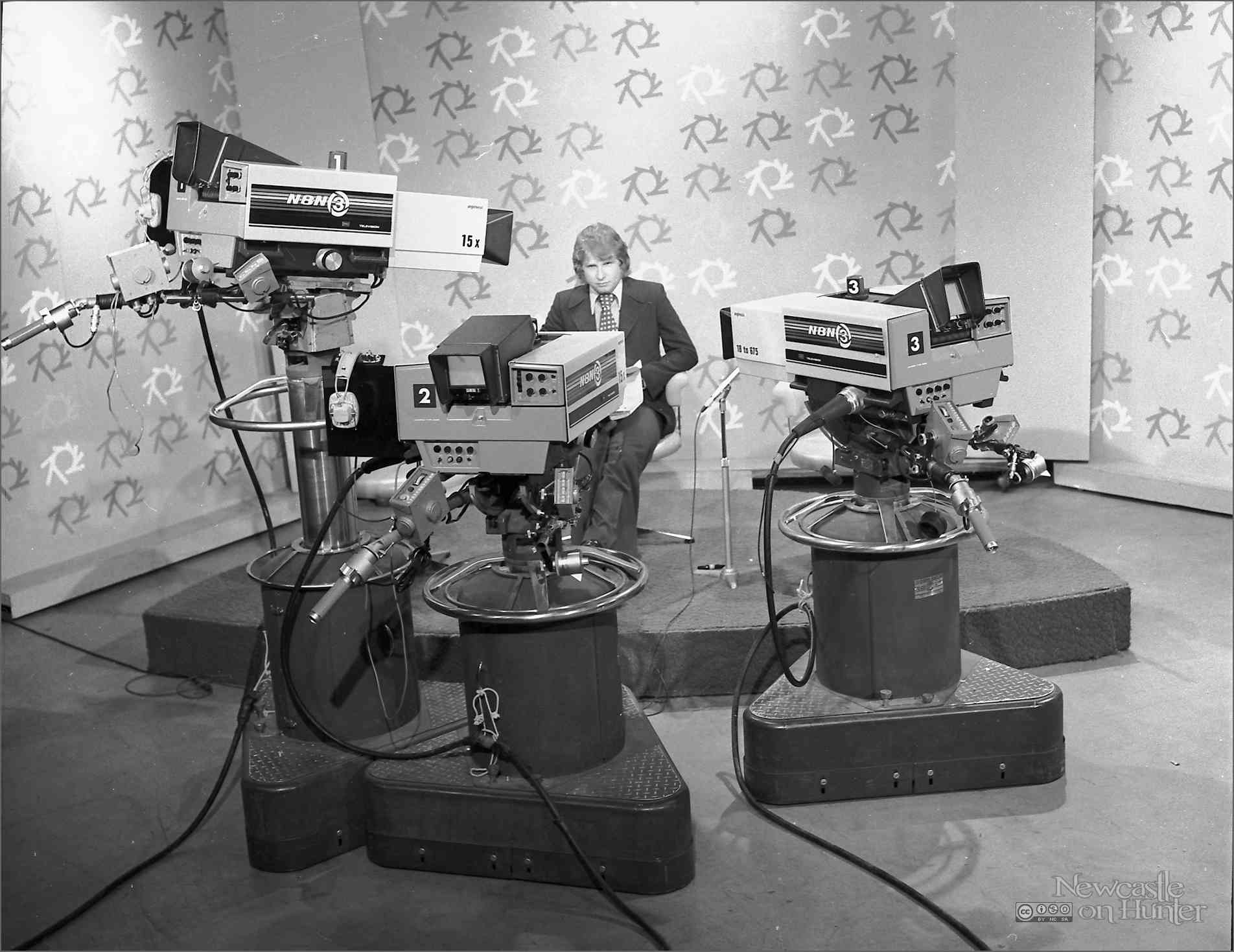

Three EMI cameras were deployed in Studio A, two in Studio B, and two in the OB van which borrowed one or more from the studio should the event require it.

Above ~ Commissioning engineers with the camera control unit (CCU) at top and its huge power supply at the bottom. Various test gear in the middle.

Below ~ Director Dennis Busch and EMI engineers with a new camera on the set in Studio A.

Rod Prout’s subtle expression says he’s not the least fazed by Ian Hill’s larger-than-life flamboyance. And Ian seems quite comfortable, looking good, in collar and tie.

Rod grapples with the new gear. A dapper sales engineer assists.

Wal Morrison, surrounded by three EMI Daleks, waits patiently until the promotional photographs are done.

Technician Dave works on one of the OB unit's EMI 2005 two colour cameras. A third was borrowed from the studio as work required.

EMI used three one-inch camera tubes, one for each colour channel. EMI’s vidicons used a lead oxide sensor array and were thus termed “plumbicons.”

Videotape

The monstrous RCA-TT monochrome videotape recorders operated for over a decade when, to everyone's relief, they were replaced by colour videotape machines from Ampex.

We interrupt transmission to give a brief overview of videotape.

Squeezing moving pictures onto magnetic tape demanded far more "tape" than sound, which is why videotape is (was) so wide. Smaller portable VCR's (video tape recorders) used one inch wide tape, but from the start heavy studio equipment employed tape that was two inches (50mm) wide. Audio tape on reels was only a quarter inch (6mm) wide.

Tape also had to move past the heads much faster due to high video frequencies. Since this was impractical (spools were limited in length) the innovation of "spinning heads" solved the speed problem by writing the magnetic track across the tape and not along it. With 4 heads on a single spinning drum, one of them was always touching the tape. That's why they were called "helical scan" - the magnetic trace was literally helical in space. (Brain hurting yet?) And it’s also why such wide tape was needed. And why machines were so big - 90 minute 2 inch tape reels were very, very heavy.

By which tedium we can segue to this curious factoid:

Radio station 2KO (you might know it as "KOFM" assuming you actually know or care what a “radio” station is) like all broadcast stations must, by law, record their transmissions. Not for posterity, but as evidence in a dispute.Radio 2KO's equipment rack in the 1970s. Disembodied hand adjusts an off-air monitoring radio tuner, above which is the tape logging recorder. At top right is the audio compressor. The big panel mid-left is the transmitter changeover unit.

2KO used an audio "helical scan" recorder for this purpose with the same wide 2 inch tape used by video. Each tiny tape spool held 24 hours of program. It used the same tape handling concept as videotape recorders, but turned very very slowly, and was thereby far simpler, smaller, and less expensive.

From the photos that follow, we deduce NBN went to colour with an AVR-1 and two VR-2000 machines that are always seen side by side. It’s also highly probable that an ACR-25 2 inch video cassette machine was commissioned at this time.

The pictured arrival was the Ampex AVR-1 colour machine, judging by its profile.

Arrival of an AVR-1 videotape machine. It weighed almost a tonne (2,200 lb).

This outside space would, a decade later, be enveloped by a huge Studio C.

It’s important to supervise fork lift drivers. They’re usually unsure how to lift stuff.

Above ~ From the profile this looks like an AVR-1. If the top monitoring unit was attached then it would appear this tall.

Below ~ Wild guess, but that item at left might be a recently-decommissioned RCA TRT videotape machine. Meanwhile, news cameraman Barry Nancarrow records the AVR’s historic arrival.

Below ~ VTR Supervisor Jeff Beach at left, engineering chief Harry McPhee at right

Above ~ A pose for posterity before the shiny new AVR-1

Below ~ VTR technician ‘Tiny’ commissioning one of the new VR-2000 machines. These high-band colour videotape recorders had been perfected for the 625-line television system in 1964.

One of the most significant milestones of broadcast videotape history was when Ampex and RCA developed cassettes employing the industry standard 2 inch (50mm) wide magnetic tape.

Ampex’s ACR-25 appeared in 1970 with a price tag of over U$150,000, or over A$200,000 at the time. And historically that price is roughly one twentieth of today’s dollars.

The tape was drawn from the cassette and threaded by vacuum, aligned with compressed air jets, and ready to play well before even a 5 second “spot” (promotion, advertisement) had finished playing on the transport’s other bay.

These machines were legendary and (teething troubles aside) much lauded by VTR techs around the world and now mourned for the scarcity of surviving examples.

One night there were screams from VTR so I followed the station duty tech in at a brisk pace to find one of the ACR machines screaming only slightly louder than the operator.

It sounded like a hammer mill.

When the tech opened the tape door (where the cassette is threaded over the heads) out blew hundred of shards of 2 inch tape filling the room like brown confetti. It was one of the best examples I’ve seen of a machine chucking a hissy fit.

The operator and I were horrified.

But the tech, Geoff McRae, who was never fazed by anything - had a different take. He just stood there and laughed.

Photographs of the first ACR-25 seem to match the time period of the reel to reel acquisition. A second ACR came later. These machines revolutionised the use of commercial and promotional "spots" that had to be tightly scheduled for program commercial breaks. Even one ACR was a life-saver, but two enabled huge flexibility and production capacity.

Below ~ NBN co-owner Michael Wansey (left) and General Manager George Brown with NBN’s new ACR-25 cassette videotape machine.

Above ~ Rodney Prout (left), VTR Supervisor Jeff Beach, and (presumably) Ampex commissioning engineer.

Above ~ Technicians Irish and Stroudy prepare the Ampex colour videotape recorders for operation.

By 1977 NBN had acquired a compact Ampex AVR-2 that could be broken down into various and compact configurations, ideal for outside broadcast vehicles. The publicity photograph below shows George Brown (at right) with the new machine.

Studio & Commercial Production

With colour offering great opportunity to sell commercial time to local and national advertisers, studios A and B got their makeovers, as they promised to generate as much commercial content as program material.

The RCA vision switchers were just that - simple cut and mix. But myriad new effects were on offer with solid state equipment. effects that would both entice advertisers and satiate cravings of the station’s creatives.

Both studio control rooms got Richmond Hill Labs vision switchers. One is being unpacked as pictured below, with a rack containing some of the required electronics nearby.

Technician Chris Minehan unpacks the new Richmond Hill colour vision-switching desk.

Any equipment that could be remoted had its backend hardware installed in Master Control’s rack bay to centralise maintenance and operations. In the 70s the “backends” were still so bulky that entire racks were needed to house them.

Pictured below, in Master Control circa 1976, at left is part of the operations and monitoring console, while at right is the end of a bay of 8 equipment racks. The rack on the left contains control electronics for studios A and B vision switchers. The rack on the right is shown in the picture above and is associated studio electronics.

Never a year or two went by without a shuffle of equipment or workspaces to accommodate new equipment, processes, or someone’s thought bubble.

With that in mind, it is with the slimmest of evidence (which applies throughout this article!) that I declare the operator below is sitting at a new audio mixer desk in Studio A control, and that the existing RCA BC6 has gone to a revamped Studio B control room. I further surmise that this desk would in turn replace the BC-6 when Studio A audio control scored a mouth-watering Neve audio desk a decade later.

Russell trials the new audio desk. So many more buttons that the old RCA BC6.

The retired BC-6 spent a hectic decade in Studio A, but leisure was not to be its lot in Studio B as a nightly news audio mixer.

One evening in the middle of the news there were some loud crackles and pops in the sound off-air, then a slow 5 second fade to silence, which was relaxing, yet disturbing. Nor was it immediately clear where in the long and tortuous program path failure might have occurred - until the talkback screamed for a tech.

In Studio B control the audio operator was white faced and helplessly motioning to his totally inert audio mixer. This was a conundrum probably never planned for - a dead audio console. They never die.

Plan A was to suddenly fall ill and go home, but the expressions on the control room crew told me that would never succeed. So plan B was my only real choice - a tried and true action that is, strictly define, most definitely not a plan. It's a strategy that has existed throughout the age of electronics and has become a standard operating procedure (SOP) in the annals of computing. They even do it in the future in Star Trek.

The BC6, you need reminding, was a 1950’s generation audio desk full of vacuum tubes, soldered wires, large potentiometers driven by operators with ten thumbs via huge Bakelite knobs.

Top center on the BC-6 is a good old fashioned mechanical toggle switch to power the desk on and off. This is extremely rare on broadcast equipment consoles. But there it was.

I switched it off and on again. Instinctively, reactively, and ignorantly, because there was no other immediate thing to do.

The desk came to life, the news audio came to life (the team had carried on as if all was ok, as they had to, of course) and everyone stopped making nervous glances at the desk and me.

Minutes later it crackled and faded to quiet again. I ran in and repeated the “fix” and this time stayed. Another 10 or 20 times the thing started to die, and each time I switched it off and on again, both according to electronics lore and by imperative.

For the slow fade to oblivion - and not an ignominious abruption - appreciation is expressed for the over-size electrolytic capacitors on the high voltage DC rail, and the graceful dwindling of emission in those big glowing tubes.

And what amazes till this very day is why the innards of that mechanical switch didn’t collapse, arc the mains voltage, and disintegrate in a brief and final microsupernova - along with, in all likelihood, my job.

For which I’m eternally grateful.

Mentioned earlier, connecting those expensive videotape, telecine machines, and studio cameras to the program path required hundreds of thousands of 1970 dollars worth of ancillary gear. Television signals didn’t just float around the cables. They needed to be timed, refined, amplified, and combined.

The heart of a TV station was a device generating a master signal for television electronics called a synchronising pulse generator (SPG). Although in a few years time new racks would carry slim, attractive blue-panelled boxes bearing the Leitch brand - with exotic model types like Time Code Generator and Colour Bar Generator, and Master Clock - in 1975 the station relied on an aging German SPG.

In the old days we shut NBN down around midnight when program ended. One night before going home I decided it was a good time to replace a blown lamp in the Fernseh SPG (if memory serves that name correctly).

BIG mistake.

Removing a lamp (there were dozens) meant, bizarrely, that two contacts feeding voltage to the lamp closed and touched. Also known as a short circuit. The power supply hadn’t heard of short-circuit protection. It blew up.

Being the ONLY SPG for the station - and TV stations don’t run without an SPG - I worked for hours fixing that arcane, convoluted supply so we could, you know, switch the TV station on the next morning.

One wonders how the station managed to run for 15 years without anyone inadvertently killing the studio by choosing to change a lamp whilst on air. I certainly do.

Telecine

The new colour equipment was and still is, despite its patent obsolescence in our modern digital world, most impressive in appearance and operation and, so often the case back then, wonderfully over-engineered.

The “telecine” machines pictured here are one such example of brilliant, reliable engineering. Telecines convert celluloid movie film (16mm in NBN’s case) to electronic television signals.

Pictured ~ Technician Vicki loading and checking film on the telecine circa 1976.

NBN acquired three Rank Cintel Mk II flying spot telecine chains that could play 16mm monochrome, colour negative, and colour positive film. They were extensively used for movies at night, news film during bulletins, and commercial production or studio productions’ media during the day.

Reader Michael supplied a correction, just the sort of feedback welcome, which can be sent (and discussed) via email to Throsby.

I read through the section on TELECINE, and noted the units photographed are Rank Cintel Mark II chains, NOT Mark III as quoted.

The MkIII (released around 1976) stood more like the Ampex AVR-1 VTR with a sloping glass covered deck, with electronics underneath rather than in racks alongside.

The Rank Cintel Telecine machines were great workhorses, fully earning their keep for almost two decades until beancounter ROI - and computers - swept them into history.

Technician laces 16mm film on one of the three Rank Cintel Mark Two telecine chains. A fourth machine was similar except it had a 35mm slide handling mechanism used for commercial slides, promotion graphics, and keying captions.

Earlier models of the film-to-television conversion process sent light from a high-intensity lamp through a slide or moving film to project the image onto a vidicon camera.

NBN’s Rank Cintel telecine machines used a high-precision TV screen as a light source (it bore an X-ray warning!). At any given instant in analogue TV there is no raster (picture) on the screen but only a single spot that zig-zags across the screen so fast the eye sees only a lit rectangle - a “picture.” The moving spot scans “through” the film, and the light is split into three channels via optical colour filters. These split light beams are captured by large sensor tubes called photomultipliers.

Three channels, one for each colour, are processed and re-combined to form extremely high-quality, high-resolution reproductions of the film source.

When television broadcast technicians are tested for their certification (Television Operator’s Certificate of Proficiency), they are inevitably asked during the verbal examination what to do if the film should break during a live broadcast.

Well, let me assure you, film breaks early and often, as the glue where it’s spliced becomes brittle. It’s also spliced early and often to make the typically 90 minute film fit into each channel’s time slots. The same prints toured the nations TV channels getting cut & joined over and over.

So. the stock answer to that question is also an actual routine for any telecine operator: let the machine keep running and place a basket under the path to collect the loose film.

It’s not that simple in life. You don’t know it’s broken unless it breaks leaving the supply spool or before reaching the optical gate - and that isn’t fun. But if it breaks on the take-up end, the machine will likely not start after a commercial break. Slightly more fun.

All in all, the worst thing that a telecine operator has to contend with is getting home after working a shift, switching on the TV (mistake) and seeing the station publicly apologise for the movie reel sequence being wrong. The movie he or she loaded before going home.

NBN’s fourth Rank telecine machine was identical except the film drive mechanism was replaced by a 35mm slide handling system comprising two trays (24 slides each, I think) to allow operator loading of one while the other was active.

Above ~ The only surviving bit of NBN’s Rank Cintel colour slide chain is but one of its consumables, a 35mm slide that once kept it company during those long weary nights.

Slides were used all day for on-air program and in between for commercial production. Other than colour photographic slides (commercials) the chain provided captions that could be keyed over the outgoing vision. You still see that today at the bottom of TV programs, except they’re computer generated.

Speaking of Film

Well before my time, so with a little speculation yet again, it’s assumed that building was extended (as indicated in the leading aerial photograph) for multiple reasons. On the ground floor the existing film processor clearly had to keep supplying nightly news footage while the new colour lab was installed.

Below ~ NBN’s original film processor. Unfortunately the only parts of this picture in focus are the scratches and debris on the scanned negative.

The expanded area included not only the new colour film processor shown below, but ventilation plant, and a series of dark rooms for stills handling, now in full demand for commercials photography.

Below ~ A tour of the film lab reveals an incredible amount of plumbing to handle the chemicals, aircon for temperature control, and ventilation and fumes disposal for the operator’s survival.

Above ~ Michael Wansey, George Brown, and Operations Manager Max Donnan (right).

Below ~ Michael and Max exchange pleasantries.

Above ~ News cameraman Glenn Cook operates the new 16mm colour film processor.

During the 6pm news, about 5 minutes before a story was to air that included local vision, a runner would arrive in telecine breathless with their dash from the film processor, brandishing a spool of 16mm colour neg film.

"Quick, this is what they're waiting for. It's force-processed so could be a bit grainy." Understatement!

News

Which brings us to the News Department.

The news here is that the archive is bare, except for a few publicity photos. I guess a department with its own camera pool kept memories close to home.

Below ~ The NBN news camera team circa 1975 and their two Ford Escort MK1 vans. Yes, cine cameras. It’s still film, but it’s colour film! Barry Nancarrow (front left) names the others, and tells in great detail the times he had with this legendary crew in his book. The book can be either purchased or read online for free.

Although the news department was greatly affected by the arrival of colour, it had little effect on their work flow at that time. The colour film processing was just another operational system, along with studio cameras, telecine, and videotape.

It’s no put down to say that the day after NBN3 went colour, a TV journalist’s desk differed little from the day the station opened in 1962. Modern electronics was yet to work its way into The 4th Estate.

A reporter’s desk still featured a mechanical typewriter, a rotary-dial telephone, and a waste paper basket full of bad copy. Somewhere in the background a teletype chattered out the wire, oblivious to a changing world it spoke of. Across the room a Bearcat scanner spluttered emergency updates to someone’s misfortune.

Colour film went into the cine news cameras instead of black and white stock. In the studio at 6pm, newsreaders regarded shiny new cameras, a colour floor monitor, and perhaps their partner’s sense of colour coordination.

Then, like every other night for the past 13 years, they picked up and read typewritten copy to the lens.

It was 1975.

Below ~ In 1985 journalist and newsreader Anna Manzoney’s office was, yes, still rotary dial phones, mechanical typewriter, papers, etc.

Around the time of this photograph of Anna, NBN was preparing to “go digital” with a BASYS news system that employed servers with Digital VT-220 terminals for the journalists. This streamlined news scripting and creating a news rundown but little else, being a text-based system.

About a decade later it was replaced with an ENPS system that could interface with the live studio news. At last journos had real PCs on their desks (Dell Dimension 433 were their first) for email and browsing that new-fangled “Internets” - such as it was back then. Hang on, we’ve jumped 20 years into the future.

Master Control

This space was, in its day, quite the epitome of television awesomeness.

Quaint on today’s mega-playout scale, visitors on tour were always mightily impressed by its über-technical ambiance.

To find oneself commanding this nerve centre on the first day of employment - yesterday, a nobody on the street, today the most important (if most ignorant, being a trainee) person in the station - well, it was quite the buzz.

During an off-air “emergency,” while pale-faced techs ran in circles and a hapless MCR operator faked nonchalance, the room would quickly and quietly fill with assorted passersby attracted by commotion, who pressed discreetly against the back wall lest they be ordered savagely from sight.

Should the emergency persist or, worse, escalate, management types would materialise within the audience, pondering which technician might feature in the subsequent inquisition.

Below ~ In 1974 or thereabouts, technician (John Hills, far right) works on the new Master Control console. The touring sophisticates seemed not hugely impressed, despite John Kidd’s heroic attempt to direct their imaginations to the future. It was a depressing room prior to colour.

A year or three later, carpet tiles down, power on, steady as she goes, and technicians trial the freshly-minted master control room at NBN’s Mosbri Crescent studio in 1975

Above ~ John at left, Don at right, in the fully operational new colour control room.

The Master Control room (MCR) is termed “Presentation” in some US contexts, but at NBN “Presentation” applied to a program playout room, where an operator put sources to-air according to the station log, a document listing second by second what is broadcast.

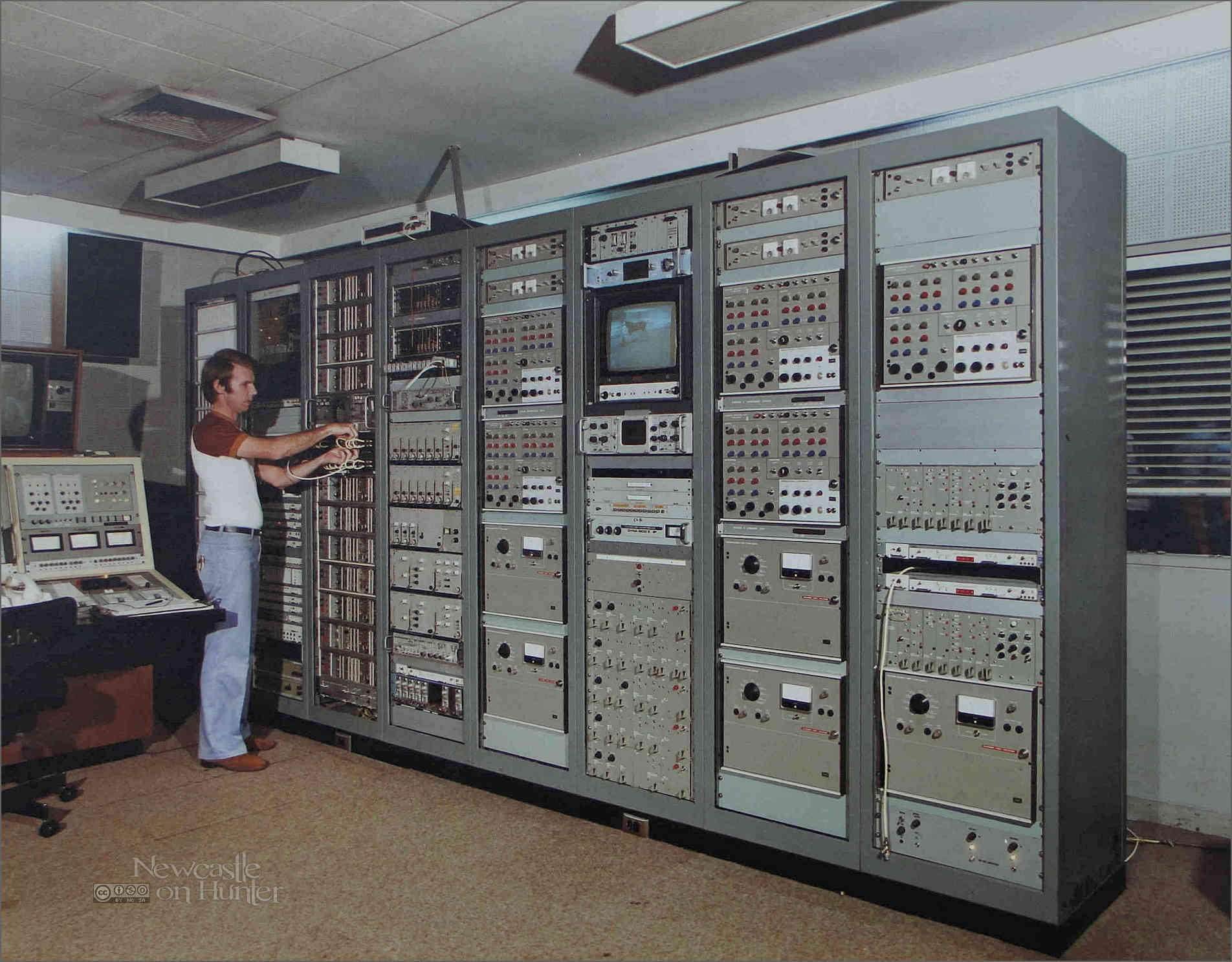

NBN’s MCR was built from scratch for the impending colour operation. Almost everything visible in these photographs was purchased for colour. Very few legacy items survived the refit.

Below ~ A rare photograph showing the entire Master Control rack bay as it was, purpose-built for colour. MCR operator “Bruce” patches something for the photographer.

For nerds, in the 8 racks above, from left:

1. Studios A & B Richmond Hill vision switchers’ electronics for studios A and B (obscured by operator).

2. At top something old. At bottom, ancillary processing electronics for the Richmond Hill gear. Somewhere in this lot is Grass Valley gear, but I forget what it did, despite the unforgettable name.

3. A full rack of removable electronics cards that are for what, I no longer ken. Perhaps as they’re removed, HAL’s personality disintegrates and he starts to sing Daisy Daisy.

4. Black units at top were stabilising amplifiers. The five large grey units are (almost certainly) the Fernseh sync pulse generator (SPG) that kept a tech up all night after he foolishly tried to change a panel lamp.

5. EMI Cameras 1 & 2 control units (CCU) with matching power supplies below.

6. At top, a precision off-air receiver (“tuner”) locked to NBN’s frequency, and connected to a broad-band stainless steel antenna on the roof. It’s the one that ran without automatic gain (AGC) so that actual signal strength would display on the oscilloscope hanging off it. Under it, the blue unit, is a Decca (or EMI) receiver with, yes, a domestic TV’s rotary tuner, and built-in audio. At bottom are lots of grey thingies.

7. Cameras 3 & 4 (Studio A #3; Studio B #1) and power units.

8. Studio B camera #2’s CCU and PSU, and more grey thingies.

Across the tops of racks 5, 7, and 8 are meter units for the cameras.

On top of rack four (literally, on the top) is a frequency meter displaying station colour subcarrier at 4.433618.75 MHz in glorious Nixie tube amber.

Below ~ Finally, as NBN colour broadcasting begins, the colour master control room swings into operation. Nat at left on camera control, Don on the Teknis keyboard, and the jury is out but it’s probably Bill over at the racks.

In the colour photograph above, technician (foreground) operates NBN Engineering’s first IBM-compatible PC (a Lanier) running a Teknis system to remotely control and monitor Central Coast translators and transmitters. Nearest at right is a remote HP terminal for (Mosely, I think) Mt. Sugarloaf transmitter control. At foreground left is AWA 2-way radio communications base station.

Operator (at left) is adjusting EMI colour camera remote controls for exposure and colour balance. Behind her chair in the console are remote panels for the three Rank Cintel telecine machines.

Technician (background) works the cameras’ control units (CCUs), visible either side of him in the equipment racks.

The room was carefully lined with achromatic greys. Daylight fluorescent lighting (5,000K) intended a neutral effect on operator’s colour perception, as the room was constantly engaged in colour grading decisions. The colour monitors were were key to that. Early models (Prowest, I’m looking at you) drifted terribly and despite daily calibration, an operator often relied on several for a consensus! Fortunately, unwanted colour frequencies could be seen in the waveform where they had no place to hide and could be visibly nulled out.

The stills photographer - to answer your “but.. but..” - had deployed some warm studio sunlamps for his promotional shoot, revealed by the change of hue across the ceiling.

Outdoor Broadcasts

A more spacious Bedford CF model was fitted out to carry lighting gear and crew. It replaced the trusty CA van that had hoped for a quiet life on city deliveries, but got worn out lugging heavy equipment across Australia’s boundless countryside. A commercial production van was effectively invisible going about its jobs, until it was partnered with the OB truck, when was suddenly called “OB2.”

Below ~ NBN's commercial production van

Colour had arrived in time for many great television occasions.

At dusk on 11th March, 1977, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II opened Newcastle’s new regional art gallery. In attendance were HRH Duke of Edinburgh and the Lord Mayor of Newcastle, Gordon Anderson.

Her Majesty and entourage arrived at Williamtown R.A.A.F. base in the late afternoon, greeted by a dignitaries, air force and army personnel, and the royal internal combustion carriage.

Donning its OB2 cap, the Bedford joined the action, brandishing a studio EMI camera and a microwave link. In 1977 colour recording was probably too expensive and bulky to justify, or even fit, in the van. A compact Ampex AVR-2 reel to reel recorder was a future candidate, able to run from a 240 volt mains supply (at 20 odd amps!) and some compressed air.

Above ~ Technician Tiny is on some urgent task while the cameraperson concentrates on the VIP.

A bulky EMI camera, a cameraman, and a microwave transmitter jostled for space atop the van. The microwave dish pointed at Mt Sugarloaf, from where the signal was down-linked to Mosbri Crescent studio for recording and/or live broadcast.

Below ~ Queen Elizabeth II alights from RAAF 34 Squadron’s Hawker Siddeley VIP aircraft at Williamtown base on 11 March 1977.

Meanwhile, awaiting The Queen’s arrival, NBN’s freshly-painted and decaled colour OB van was parked in Laman Street near the tabernacle, having set up shop with it’s two EMI colour cameras.

One camera was placed on high scaffolding near King Street and overlooked the park. The other joined a media scrum near the gallery entrance.

Above ~ Cameraman Trev, one of NBN's longest-serving staff.

The scaffolding in Laman Street was a tight fit for a tripod-mounted studio camera, forcing the cameraman into an awkward seated position. The NBN team were having such a hard time of it they attracted the attention of Her Majesty’s Minders, who weren’t entirely sure this was a real television crew, or that was a real TV camera.

Below ~ OB crew (Joe Brown at left, Ian Hill right) juggle stuff while security gives them the once-over. On camera, Gadge tries to work in a most uncomfortable position. The press 'stand' was not one of NBN's and barely suited to TV camera work.

A setting sun sent the venue into shadow to provide soft and even lighting, which was rather fortunate for the media photographers, more so for a television camera with its limited dynamic range. The Queen is accompanied by HRH The Duke of Edinburgh and Newcastle Lord Mayor Gordon Anderson (seated).

Ceremony over, The Queen made Her way back through Civic Park to be driven to the royal yacht Britannia that had arrived in Newcastle Harbour (link to Simon James on YouTube).

While choosing the images I'm often thankful that the stills photographers in those days concentrated on the machinations of the outside broadcast preparations, and not, as a news photographer would have, on the subject of the broadcast. Otherwise it would be a repetitious assortment of close-up pictures of the queen, in this case.

Studio A Shows are Now Radiant

“Ian Nash and Friends” were Logie winners. IMDB lists the show as “1976-1979” and winning two Logies.

Responding via email (to Throsby at NewcastleOnHunter.com) John Norris confirmed the director was Dennis Busch, the host was, of course, Newcastle musician Ian Nash, and the guest immediately below is Marcia Hines.

The first show was recorded on 26th May 1975, shortly before colour television, still with the monochrome RCA TK cameras. Those below depict a subsequent colour production. Despite negatives degrading, the images are quite striking. The final image of this set is from a different show. More of these will appear in an article about studio productions.

Further above, on camera, Phil Balsdon.

Below ~ 1978’s Right On music review.

Above ~ Romper Room, and an attentive, possibly anxious, group of mums in the foreground.

Below ~ CBA High School Quiz. The question might have been funny - or maybe it was just Nev’s hair.

Advertisements in Colour

Even Big Dog had to get his hands dirty and pull some dollars for the team. He’s at BBC Hardware, in the days when Bunnings was a pipe dream.

News, Weather, Sport.. Coloured!

Why didn't Fin look any better in colour? Because he always looked good.

Above ~ John Lloyd-Green cued for camera at the Studio B news desk.

Below ~ Ray Dineen and Neville Graham during news set design and testing. It was soon apparent that blue worked better, being a complementary colour for skin tones.

Above ~ Des Hart, who made even makeshift weather sets seem elegant.

Below ~ Noel Harrison (at right) with guests on Sport Report. Noel also had a 1978 colour show called Sports Magazine.

What's in the Future?

In 1977 with colour television fully underway, NBN’s owners look to the next decade.

By 1980 the station’s building size more than doubles, as it prepares for the most prosperous and exciting period in Australian television - the heydays of the 80s and 90s.

A news chopper is in the air, portable ENG cameras are in the field, and aggregation extends NBN’s network across northern NSW to the Gold Coast.

Levering its extensive new microwave network, a telco is born that devours its parent television company.

Computerisation displaces almost everything in the preceding images, ushering a fully digital network alongside the analogue. All the while the Internet erodes revenue of free to air behemoths and a slow death ensues..

The future is now, as NBN devolves into an arm of the Nine Network, itself continuously divesting and acquiring in a struggle to survive. While traditional media - newsprint and broadcasting - succumb to the inexorable march of technology, a media-consuming population are besotted by nothing less than the latest new thing.

What goes around...

Below ~ NBN co-owner Michael Wansey (right) reviews plans for office extensions and a massive new studio. Image from NBN’s 1977 board report.

Post a Comment

Additional information, anecdotes, etc., or corrections are welcome.